LongCat -Base and -Thinking

Original paper · LongCat Team et al 2025

It's becoming a pattern: another chinese lab, seemingly appears out of nowhere and releases a massive +500B parameter model. Just a year ago, this scale of open release would have been unheard of. Hot on the heels of the base model, LongCat-Flash, they've already released LongCat-Flash-Thinking, a dedicated reasoning model. But before we get into '-Thinking', I figure we want to take a close look at the base model that underpins it. It seems I completely missed, or ignored, the talk about this model on X when it was released a few weeks ago, but writing this after I've read the paper I can tell you this is an insane release, wow, I'm thoroughly impressed.

LongCat-Flash is a 560B MoE with a dynamic computational budget allocation that allows it to activate between 18-31B per token depending on contextual demands. They report that the model is trained on over 20 trillion tokens within 30 days. This is an impressive feat of engineering, especially for a team that seems to have limited experience in the field. Let's do some quick napkin math to get a sense of the scale.

We can derive the popular 6 * num_tokens * num_active_parameters rule of thumb for training FLOPs from first principles. For a transformer layer, the cost is dominated by the matrix multiplications in the attention projections and the FFNs.

- The attention block consists of four projections (for Q, K, V, and Output), which for a forward and backward pass require approximately

24 * B * S * D^2FLOPs, whereBis batch size,Sis sequence length, andDis the hidden dimension. - An MoE FFN block activating

Eexperts, each with an intermediate size ofF, requires about12 * B * S * D * E * FFLOPs.

Combining these for L layers, plus the embedding/unembedding layers, gives the total FLOPs. A simpler way is to sum the active parameters and multiply by 6 * num_tokens. The total number of active parameters in a forward pass is the sum of the non-MoE parameters (attention, layer norms, embeddings) and the parameters from the activated experts. For a well-designed MoE model, this is dominated by the expert parameters.

Because LongCat-Flash has a dynamic forward pass, the exact compute is variable, but the paper states they activate 27B parameters on average. Using this, we can estimate the total training FLOPs:

The paper specifically mentions using H800s for their inference stack, so we can reasonably assume they were used for training as well. An NVIDIA H800 delivers around 989 TFLOP/s for BF16, but achieving high Model FLOPs Utilization (MFU) is challenging. Assuming a generous 50% MFU (495 TFLOP/s), the number of GPUs required to complete training in 30 days would be:

This is a lower bound, as we've ignored some computations and assumed a high MFU. The paper mentions using "tens of thousands of accelerators," which suggests either a much lower MFU, a much shorter training run than 30 days, or simply having a massive cluster at their disposal. Regardless, a training run of this magnitude from a relatively unknown commercial lab is a testament to the rapid democratization of large-scale AI

arch

this is a non standard MoE with a couple of modifications that are are novel in a model of this capacity.

zero-computation experts

Naturally, some tokens are "harder" to predict then others. The paper argues that such tokens should demand more resources. One can argue for this case by looking at the success of speculative decoding, where a smaller draft model is able to accurately predict certain output sequences of larger models. We've seen similar analysis earlier establish the existence of fork tokens which very important for reasoning sequences. Anyway, motivated by this theory, LC introduces a dynamical resource allocation method in the MoE layer. This is achieved by introducing new experts in the MoE which don't perform any compute and simply just let the input pass through, LC introduces of these zero-compute experts alongside normal FFN experts. This allows the model to choose how much compute to assign to a certain token. The MoE layer is formalized as follows:

Not all tokens are created equal; some are inherently "harder" to predict than others. The paper argues that these harder tokens should demand more computational resources. This idea is empirically supported by the success of speculative decoding, where a small draft model can accurately predict outputs for "easy" tokens from a much larger model.

Motivated by this, LongCat-Flash introduces a mechanism for dynamic computational allocation. This is achieved by adding "zero-computation" experts to the standard pool of FFN experts within each MoE layer. These special experts perform no computation and simply pass the input through as an identity function (). This design allows the model to learn to allocate a variable number of FFN experts to each token based on its contextual importance. The MoE layer is formalized as follows:

where are the router gates for the top-K selected experts and is the output of the -th expert.

To guide the routing and ensure a stable computational budget, the model includes a bias term in the router logic, which is dynamically adjusted using a PID controller. This is a refinement of the aux-loss-free strategy seen in other models, designed to maintain a target average number of activated FFN experts. The result is a model that allocates its computational budget more effectively—achieving a lower validation loss than a baseline model with a fixed compute budget equivalent to LongCat-Flash's average. This confirms that it's beneficial to trade less compute on some tokens for more compute on others, and that the model can learn this allocation itself.

shortcut-connected moe

Expert parallelism (EP) is crucial for scaling MoE models, as it distributes experts across accelerators. However, the conventional execution paradigm imposes a sequential workflow: a collective communication operation (all-to-all) must route tokens to their designated experts before expert computation can begin. This communication latency creates a bottleneck that is difficult to hide with computation. While shared-expert architectures attempt to mitigate this by overlapping communication with the computation of a single shared expert, the computational window is often too small to be effective.

LongCat-Flash employs Shortcut-connected MoE (ScMoE) to address this limitation. The key idea behind ScMoE is to reorder the execution pipeline by feeding the MoE block with the output from an earlier part of the transformer layer (specifically, the output of the first Multi-head Latent Attention block). This creates a much larger computational window—the dense FFN from the preceding block—that can execute in parallel with the MoE's dispatch and combine communication phases. The paper validates that this architectural change is quality-neutral, showing nearly identical loss curves to a standard MoE, but provides substantial system-level efficiency gains for both training and inference. In practice, this design choice reduced the proportion of time spent on non-overlapping communication from 25.3% to just 8.4%.

The overall transformer block structure can be summarized as:

- A dense path:

MLA_1 -> FFN_1 -> MLA_2 -> FFN_2 - A sparse path: The MoE block takes its input from the output of

MLA_1. - The final output is the sum of the dense path output (

FFN_2) and the sparse path output (MoE).

The model uses MLA, consists of only 28 layers, and contains a staggering 512 FFN experts and 256 zero-computation experts per MoE block. The router activates 12 experts per token, with a target of activating ~8 FFN experts on average. This results in an incredibly high sparsity factor of 64 (an activation ratio of 1.56%), which is higher than I've ever seen before. You typically don't see this level of sparsity due to the infra complexity that comes with it, but from what I can gather ScMoe alleviates this making it possible.

training

The training methodology also includes some interesting techniques.

LongCat-Flash uses model growth initialization, a strategy I haven't seen in a production model before. Instead of training the full 28-layer model from a random initialization, they first train a half-scale model (14 layers) on tens of billions of tokens. They then use a layer stacking technique to duplicate this pre-trained model, creating a 28-layer checkpoint that serves as the initialization for the full training run.

the team hand designs deterministic kernels that improve on existing deterministic implementations. this is really cool to see. there was a recent blog article from Thinking Machines by Horace He on this topic and how to achieve determinism. really cool to see this topic in a paper released before the blog post. speaks to the level of this team.

The paper continues with an in-depth discussion of their distributed training strategy and inference optimizations, including communication/computation overlapping, custom kernels, and speculative decoding. It's a dense and highly informative read that I recommend, but I won't cover it.

LongCat-Flash-Thinking

If you're going to be a frontier lab in 2025, you've got to be able to create a strong reasoning model, which typically means building first-rate RL infra. The LongCat team set a high bar for themselves by starting with a massive 560B MoE base model. I'm looking forward to get answers to several things: What's the training recipe, e.g what combination of cold start SFT + RL? How do you handle the negative transfer that often plagues cross-domain RL? On the infrastructure side, how do you tackle long-horizon RL tasks, especially the agentic workflows that are now central to frontier models. Finally, on the algorithmic side, how do they approach the exploration-exploitation trade-off and what tools are you using to achieve prolonged, stable RL.

cold start training phases

We begin with the LongCat-Flash-Base model. While generally capable, the authors identified its limitations in handling complex, multi-step reasoning. Ultimately, the goal is to prepare the model for large-scale RL, but before that, they introduce a two-phase cold-start process designed to unlock the model's latent reasoning abilities without degrading its foundational knowledge.

First is a mid-training phase. The intuition here stems from a key deficiency in general pre-training corpora: while vast, they contain an insufficient proportion of data from reasoning-intensive domains (like STEM and coding), and more critically, explicit long CoT patterns are naturally scarce. This stunts the model's intrinsic reasoning potential. The mid-training phase addresses this by infusing the training corpus with a meticulously curated dataset of reasoning-intensive problems, aiming to "cold-start" the model's latent reasoning abilities without degrading its foundational generalist knowledge.

Following mid-training is a reasoning-oriented SFT phase, aimed at aligning the model with high-quality, instruction-following patterns to establish a strong foundation for RL. This stage focuses on three distinct capabilities:

- General Reasoning: High-quality data is curated from STEM, code, logic, and general QA domains using a rigorous multi-stage filtering pipeline for prompts (screening, ground-truth validation, and difficulty filtering).

- Formal Reasoning: To tackle Automatic Theorem Proving (ATP), the team developed an expert-iteration pipeline integrated with a Lean4 server. This process synthetically generates a dataset of formal statements, a "thinking process" in natural language, and a machine-verified proof.

- Agentic Reasoning: The key challenge here is curating a dataset where tool use is indispensable, not just helpful. They introduce a dual-path evaluation to select queries that show a significant performance gain only when tools are available. This "tool-necessity value" is defined as , where is the pass rate with and without tools. The selected queries are then paired with high-quality, multi-turn tool-use trajectories.

rl

With its reasoning capabilities primed, the model is ready for large-scale RL.

dora: dynamic orchestration för asynchronous rollouts

RL at scale is notoriously inefficient. A disaggregated architecture (separate devices for generation and training) risks device idleness due to sequential dependencies. Conversely, a colocated architecture (all roles on the same devices) suffers from suboptimal performance, as generation is memory-bound while training is compute-bound, demanding different parallelization strategies. A further problem is skewed generation, where synchronous training forces the entire batch to wait for the single longest output—a frequent bottleneck in agentic tasks. Asynchronous training is a common solution, often breaking long responses into segments generated by the latest available policy. However, this introduces its own problems: updating the policy mid-generation forces an inefficient re-prefill of all ongoing sequences, and using inconsistent policy versions for different segments of a single response may harm convergence.

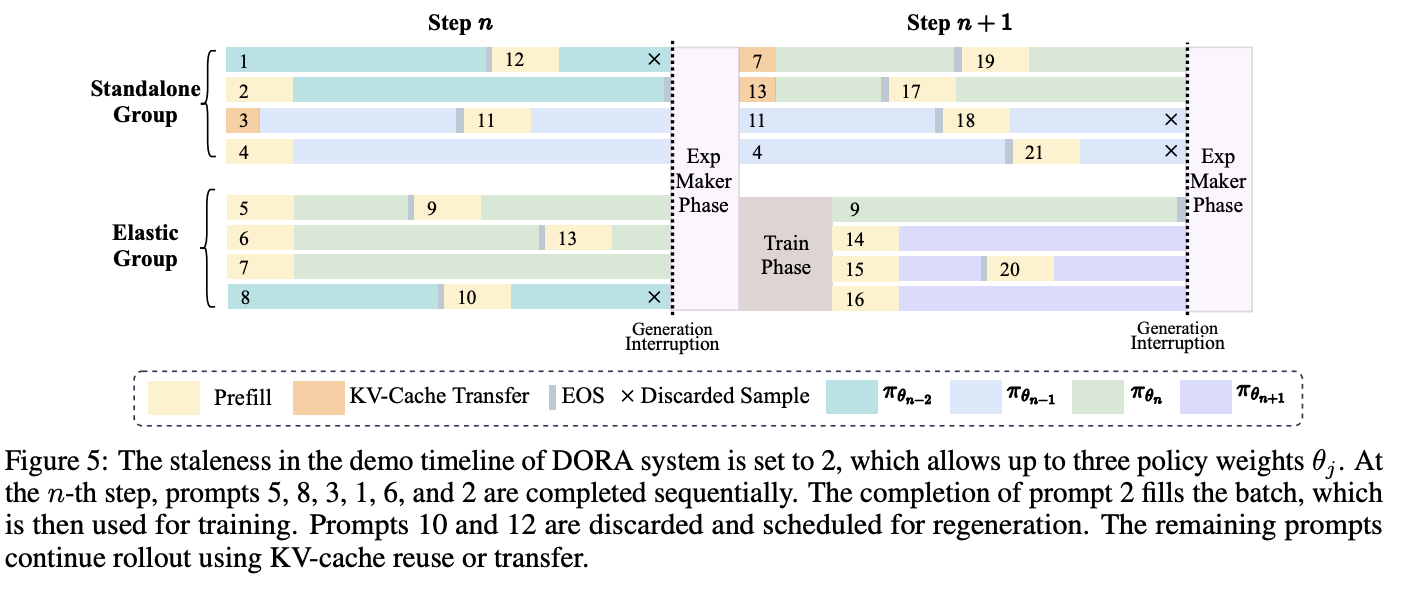

DORA is LongCat's answer to these challenges. The system divides accelerators into two groups: a Standalone Group dedicated exclusively to generation and an Elastic Group that dynamically switches between generation and training roles. The system is governed by a user-defined staleness parameter, which dictates how many older policy versions can be used for generation.

The workflow proceeds in three phases, assuming a training batch size of 6 and a staleness of 2 (allowing policies , , and to coexist):

-

Generation Phase: Both the Standalone and Elastic groups perform rollouts using the allowed policy versions. As soon as a response is completed, it's sent to an experience buffer, and the generator immediately starts on a new prompt. This continues until the buffer has enough samples for a training batch. At this point, any ongoing generations using the oldest policy () are discarded, as it's about to be evicted by the new policy from the upcoming training step (). The KV-caches of ongoing generations in the Elastic Group are saved, while those in the Standalone Group are effectively "paused."

-

Experience-Maker Phase: All accelerators are repurposed to compute log probabilities, reference model probabilities, and reward signals in parallel. Once this is done, the Standalone Group's generators spin up the inference engines and resume their paused rollouts (reloading the KV-cache) or start new ones. They may also receive a KV-cache transfer from the Elastic Group if a sequence needs to be continued with the same policy version.

-

Model Training Phase: The Elastic Group devices now assume a training role and perform a gradient update on the collected batch of 6 samples. The Standalone Group continues generating rollouts uninterrupted. Once training is complete, the Elastic Group switches back to a generation role, loading the newly updated policy weights ().

The whole process is illustrated in the following figure

DORA's design ensures that each response is generated entirely by a single, consistent policy, which improves convergence stability and reduces the overhead from re-prefilling. It also achieves near-zero device idleness by eliminating the skewed generation bottleneck; the only inefficiency comes from the discarded samples using the oldest policy.

algo

LCFT is trained with a modified GRPO

- The KL divergence term in the loss is removed. GRPO, when introduced by DeepSeek, moved the KL divergence penalty from the rewards directly into the loss function through a KL divergence between the learned policy and the reference policy. However, it has been shown that the gradient of this term, (the KL estimator) ends up being biased.

- Applies the Dr.GRPO fix of calculating token-level loss, utilizing a global constant of maximum generation length as the denominator when calculating said token loss.

- Utilize Truncated Importance Sampling to mitigate the distribution mismatch between inference engine and the train engine. This method was only publishes a bit over a month ago so they must have just recently finished the RL training.

The standard GRPO objective is:

LongCat-Flash-Thinking is, as expected, trained with a modified GRPO. Several key modifications are introduced, primarily targeted at stabilizing asynchronous training.

- The KL divergence term is removed. The standard estimator used for the KL term's gradient has been shown to be biased during optimization despite its unbiased expectation.

- It adopts the token-level loss formulation from Dr.GRPO, using a global maximum generation length constant as the denominator.

- Truncated Importance Sampling is used to mitigate the distributional mismatch between the inference and training engines.

- A triplet clipping scheme (, , ) is employed to bound the importance ratio, preventing unbounded variance and model collapse, which is especially critical for sparse MoE models where expert routing can change between policy versions.

The final objective function is:

rewards

For non-verifiable tasks like creative writing, LongCat-Flash-Thinking uses a standard discriminative reward model.

For verifiable tasks (e.g., STEM), they depart from typical rule-based systems and instead use a Generative Reward Model (GenRM). This model compares the reference answer with the model's response and generates a natural language justification for its correctness judgment. This allows for more flexible evaluation, accommodating various equivalent expressions (e.g., recognizing that is the same as ). The GenRM proved far more accurate than alternatives on a human-labeled test set, achieving 98.8% accuracy compared to 94.0% for a non-reasoning GenRM and just 80.9% for a rule-based system.

training

As others have found, performing RL on a mixed-domain dataset is difficult. The large distributional shift between batches from different domains (e.g., short general QA vs. long agentic traces) often leads to inefficient training and sub-optimal performance. Sequential training can mitigate this but is inflexible and prone to catastrophic forgetting.

Instead, the team adopts a domain-parallel RL approach. They train separate expert models for distinct domains (STEM, Code, Agentic) and then merge them into a single, nearly Pareto-optimal model. The merging strategy is a three-pronged approach to mitigate parameter interference:

- Normalization: The magnitude of each task vector () is normalized to balance the contributions from different domains.

- Dropout: Inspired by DARE, dropout is applied to the delta parameters () to prune redundant values.

- Erase: Inspired by SCE, parameter elements where the update direction conflicts across a majority of experts are erased.

Finally, the merged model undergoes a final alignment phase using RL on a general domain dataset. This step enhances its capabilities in broader scenarios like instruction following and reinforces safety guardrails after the fusion process.