what i've been reading

August 28, 2025

Been a while since my last update. summer is usually slow, paper wise, so haven't been reading as many papers, and the things I've been reading have been too long form for a writeup, its mostly been personal note taking. Highly recommend How to scale your model from DM and The Ultra-Scale Playbook from HF, been the best reads of the summer. what else have I been enjoying?

Why Stacking Sliding Windows Can't See Very Far

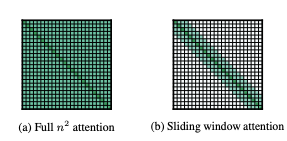

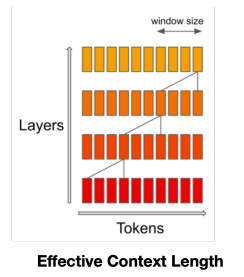

Great analysis of what actually happens to the receptive field when stacking SWA layers. SWAs are a popular method to reduce attention computation to . Assuming a context length , instead of attending to every position in the sequence, we shorten the "window" to meaning each position only sees the last W positions. The idea is that stacking these layers creates a sliding window that in theory can capture information from the entire context because the receptive field is .

Theory is great, but what happens in practice? Guangxuan investigates, and unfortunately, as it commonly is, reality is gloomier.

The idea is to analyze what the actual, or effective, receptive field is. How much influence does a token at position , apply on a token at position ? Is position 's influence bounded, or can it effectively influence any subsequent position similarly to a full attention pattern? This analysis is made easier if we make an assumption about the attention that is applied to each position within the visible window. A simple assumption would be that the attention weights are evenly distributed, so for example, in full attention where our context window is , the attention weights to each position are . For SWA, there are only visible positions, giving .

Let be the influence a word at position has on the computation at position after going through layers, where . These influences must sum to 1.

Case 1: Pure SWA, no residuals.

What happens in the simplified case where ignore residuals and only apply SWA.

As we established above, the average influence at each position is . Any token influences the current position by propagating through all intermediary positions, meaning to influence position from distance , information can first travel to any intermediate position then hop the remaining positions. Mathematically, this influence at layer becomes a convolution

which after many layers can be approximated by a Gaussian. You can see this by thinking that at every layer, influence hops a random distance {0, W-1}, and the total distance that information travels after layers becomes a sum of independent such hops. The Central Limit theorem tells us that the distribution of this sum will approach a Gaussian.

So, we know how to model the influence, but what does that tell us about the receptive field. Well, we can imagine that the effective range of this model being the standard deviation of our Gaussian, which is calculated to be:

This is important, even without residuals, the effective range of our model only grows as the square root of the depth, not linearly () as we theorized earlier. The reason for this is information dilution, as information spreads through layers, it gets averaged and re-averaged, dispersing across many positions. That is the cost of not allowing direct connections between your token positions. Imagine the influence of a token at with . This information needs to perform 10 hops through intermediary positions before reaching our current position, but at each hop, the information is averaged with other tokens attending to the same positions. This is the dilution.

Case 2: SWA + residuals

The situation gets worse when we factor in residuals, which we should point out are necessary for stable DL training at this point. The behavior when we add residuals can be modeled as a weighted average:

because of the normalization that is typically applied after the residual. Here is the conceptual strength of the residual path, typically very close to 1 (0.9 - 0.99). We have two parallel paths for information, the direct path through the residual (of strength ) and the attention path (of strength ).

The key observation here is that the attention path now also has to fight against the factor at each hop, further diminishing the influence. This factor suggests that the influence from a distance d is bounded by an exponential decay:

where is the decay rate. This upper bound behaves like a very good approximation of the actual influence. Unfortunately, this is terrible. Assuming that an influence of 1% of original strength is a good approximation of effective range, we can calculate when this happens under the exponential decay:

with the key observation being that this does not depend on . Assuming a generous , the effective range is only . Read that again, . Only twice the size of our sliding attention window.

But why doesn't adding layers help? If we have 10 layers with thats a theoretical receptive field of 100,000 tokens, doesn't that matter?

No. Because the exponential decay creates a fundamental barrier on the information as it hops along the context closer to the current position. Even if information could travel 100,000 tokens, which would require 100 hops, the influence is bounded by

The information is effectively lost at this point.

Key Takeaways

Without residual connections the effective range of stacking SWA is

The information is diluted through Gaussian spreading and the range grows with depth, albeit not linearly as theorized.

With residual connections the effective range of stacking SWA is

which to give concrete examples is for and for . In this case, depth does not extend reach.

This is why hybrid architectures are so important, you need to alternate between full attention layers and SWA. This allows you to overcome this exponential barrier, providing a path to truly long context without sacrificing the training stability that high residual weights provide within a block.

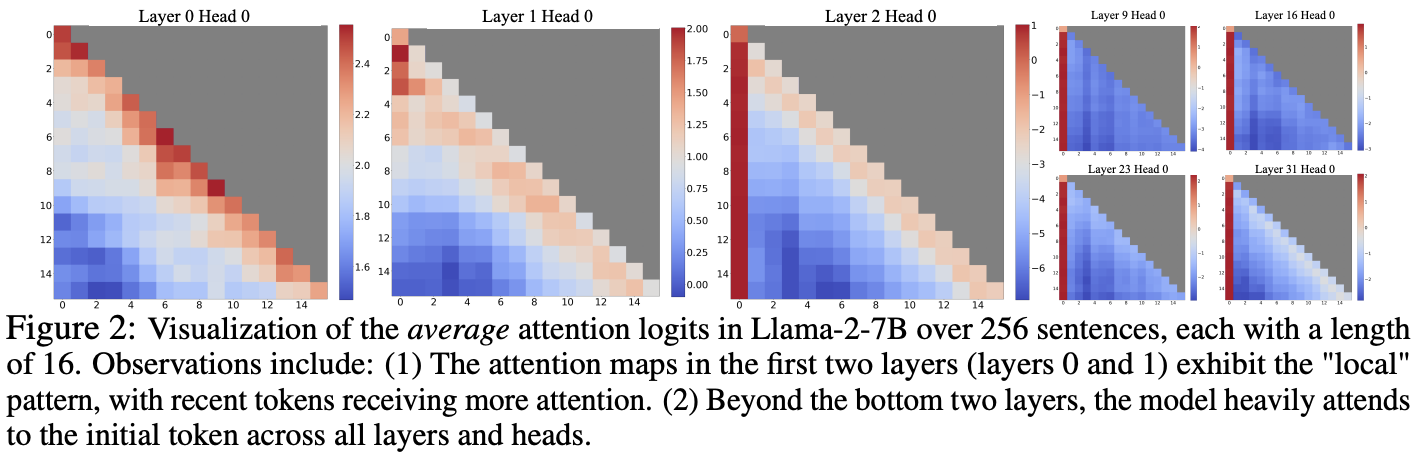

Attention Sinks

Models have a tendency to place a lot of attention on the initial tokens of the sequence, particularly in deeper layers. Why? Either the initial tokens hold significant detail to decoding the sequence, or the model learns a bias toward their absolute position. A simple experiment where the four first tokens are substituted with linebreaks ('\n') indicate that the model still emphasizes these linebreak tokens. This suggests that it is the position of the starting tokens that matter, rather than their semantic value. The authors term this concept attention sinks, and attribute this as a symptom of the SoftMax normalization. The model uses the sinks as a way to dump unnecessary attention weight which it doesn't want to distribute on "actual" tokens.

In window attention, as the first tokens are dropped from the cache, performance plummets, likely due to the disappearance of these attention sinks. Reintroducing these initial tokens by appending them to the cache does indeed recover some of the lost performance.

This phenomena isn't new, there are papers dating back to the BERT days which identify that "a surprisingly large amount of attention focuses on the delimiter token [SEP] and periods", which was argued to be the model performing a no-op. A well received paper in the vision world is Vision Transformers Need Registers which found that models would use uninformative background patches as computational scratchpads.

In the StreamingLLM paper, the proposed solution was creating a new Sink Token which would be appended to the start of every sequence during pretraining. Then, during streaming inference, you permanently preserve the KV cache of this sink token while maintaining a sliding window for the rest of the sequence.

GPT-OSS also addresses this issue, attributing the findings of attention sinks to the StreamingLLM paper. However, their solution differs slightly from the above. OAI have a simpler but arguably less flexible approach. All they do is add a single scalar parameter per attention head that acts as an escape valve for the softmax.

# S = torch.nn.Parameter(torch.empty(config.num_attention_heads))

QK = torch.cat([QK, S], dim=-1)

W = torch.softmax(QK, dim=-1)

improved understanding of sinks

several papers since the original StreamingLLM paper aid in deepening our understanding of these sinks.

Barbero et al argue that sinks serve as pressure valves, preventing over mixing of embedding states and the spread of information across tokens. The result are more stable embeddings. The effects are more pronounced in larger models, for example LLaMa 405B shows attention sinks in 80% of its attention heads.

Gue et al reiterates the fact that sinks are a fundamental constraint of softmax normalization. When attention weights must sum to 1, models naturally create a default place to allocate their attention budget. Replacing the softmax with other attention operators that don't have this constraint prevent sinks from forming entirely.

Sun et al introduce learnable key and value parameters (KV biases) into their attention mechanism, finding this design could alleviate the massive activations seen during inference - essentially the same approach as the learnable sink experiments.

Sinks typically lead to massive activations, which pose a problem for quantization because of the activation outliers.