Reading Roundup

March 30, 2025

Mechanistic Interpretability (MI) offers a valuable lens for understanding the internal operations of neural networks, especially transformer language models. It is, however, a lens, not the definitive view, and like any tool, MI has significant limitations. Its approach often involves a microscopic examination, analyzing specific, isolated components or behaviors to extrapolate broader operational principles. This focused scrutiny means many MI findings function as 'existence proofs'—concrete evidence of particular mechanisms in specific contexts. While such discoveries are insightful, generalizing them requires caution, as it's easy to shift from empirical evidence to speculation. Furthermore, the necessity of studying simplified or reduced model subsets to make interpretation tractable inherently risks introducing observational bias and may not capture the emergent complexities of the full system.

Anthropic: On the Biology of Large Language Models

Multilingual Circuits

Neural networks have highly abstract representations which often unify the same concept across multiple languages, this is well studied but how these interact provide us with a clearer understanding of the flow of a latent through the transformer.

Consider three prompts with identical meaning in different languages:

- English:

The opposite of "small" is "->big - French:

Le contraire de "petit" est "->grand - Chinese:

"小"的反义词是"->大

analyzing the features, through what Anthropic calls attribution graphs, we find that there is significant overlap in the internal computation through overlapping "multilingual" pathways:

Notice how there is a language specific component separate from the shared multilingual components. The circuit works similarly across languages: the model recognizes, using a language-independent representation that it is being asked about antonyms of "small". This mediates a mapping from small to large, in parallel there is a feature track for the language which triggers the language-appropriate feature in order to make the final prediction. However, by inspecting the features we find indications that English is mechanistically privileged over other languages as the "default". The multilingual "say large" feature has stronger direct effects to "large" or "big" in English compared to other languages. We've seen this before (!) and it further established the notion that the models concept space is biased towards the english subspace likely as a result of biased pretraining.

The language pathway is interesting because it implies the existence of such multilingual features. To further prove it's existence, the authors identify a collection of antonym features in the middle layers of the model and similarly find synonym clusters in the same place. These features are identified through english prompts only. Then, prompting the models in using the same prompts as before, but this time negatively intervening on the antonym feature substituting in a synonym supernode, they find that the resulting output is a language-appropriate synonym! This demonstrates the language independence of the operation component in the circuit! The same procedure can be used on the prompt operand: small -> hot to derive language-appropriate antonyms of the word hot, and finally on the language itself, changing the output language to Chinese, French or English purely through modification of the language feature.

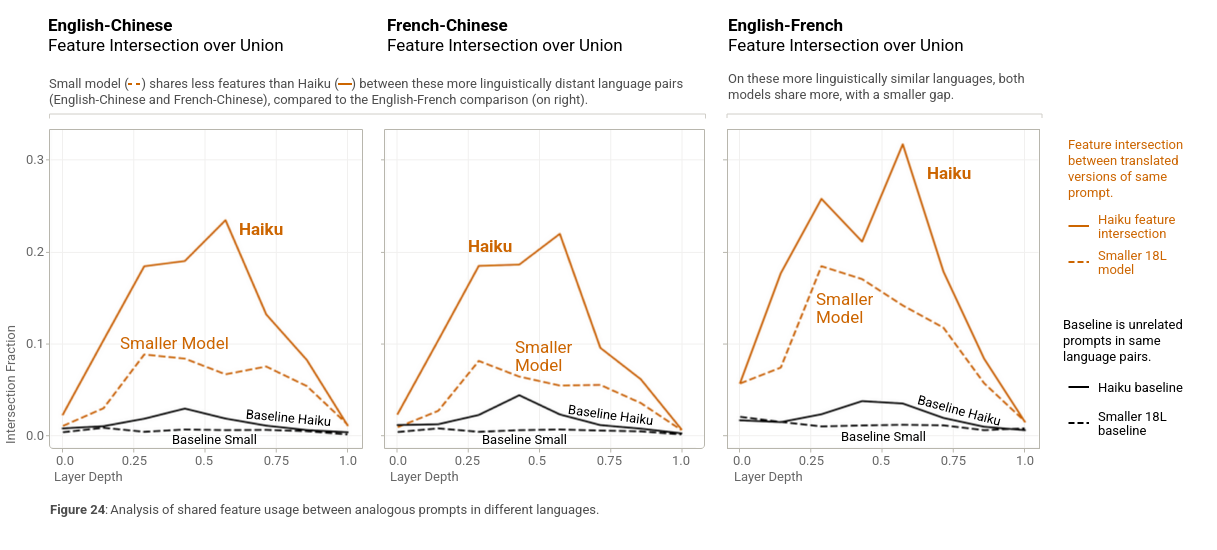

Taking the above to the extreme, one can look at large paragraphs of translated texts in a bunch of different languages, and look at the amount of overlapping features which activate at any point in the context. For each (paragraph, pair of languages, model layer), we compute the intersection (i.e the set of features which activate in both), divided by the total set of features which activate in either to measure the degree of overlap. If you do this for paragraphs which are direct translations of eachother and unrelated paragraphs in the same language pair you get a reference baseline for your comparison.

De-tokenization layers. The early layers of a language model are involved in mapping the artificial structure of tokens to a more natural semantically meaningful representation. Many early neurons respond to multi-token words or compound words.

Re-tokenization layers. In reverse, the final layers of language models mediate conversion of words or contextualized tokens back into literal tokens of the vocabulary. There are neurons which convert or dictate a representation of the word into constituent tokens one by one for output.

This is why depth is important. This coincides with the token energy discussion seen before where the overall latent vector is mostly orthogonal to the token space throughout the early -> middle layers. While the features represented in the middle layers are multilingual they are mostly aligned with english as a result of biased pretraining. English is privileged in a way where the default output is English but the representation space is large, even though English is privileged doesn't mean models think in English.

Do Llamas Work in English?

An mechanistic investigation into the latent language of multilingual transformers. Language models are primarily trained on English text, with a heavily biased distribution. Despite this they achieve strong performance on a broad range of downstream tasks, even in non-English languages. How do they achieve this generalization? This paper analyzes this through two distinct views. First, the premise, consider a translation task from french to chinese with the following few-shot prompt (where "中文" means "Chinese"):

Français: "neige" - 中文: "雪"

Français: "montagne" - 中文: "山"

Français: "fleur" - 中文: "

with the guarantee that the expected chinese translated word is a single-token word. This setup allows us to solely analyze the latent at position , as it carries all the information necessary to produce the chinese translation.

The first method of analysis is a logit lens. A logit lens approach means that we take the models unembedding matrix , which is normally applied after the final layer to get the logits which are turned into a next-token distribution, and instead apply after an intermediary layer . This gives us an inspection tool to look at what tokens the model thinks is most probably as the latents travel through the model! This is very cool. Let us track the probabilities of the English translation word and the Chinese translation word throughout the layers, are we using english as a pivot language when performing this translation?

We find for the first half of the models layers, neither the chinese or the english analog garner any noticeable probability mass, then around the middle layer, english begins a sharp rise followed by a decline, while chinese slowly grows and, after a crossover with english, spikes on the last five layers. Wow, that is really cool, it does seem like english is used as a sort of pivot language. Looking at the entire next-token distribution throughout the layers, through entropy, we see that the first half layers is a uniform distribution with an entropy of ~14 bits (vocab is 32,000 so this makes sense) and then, at the same time as the english analog spikes in probability, the entropy sharply drops and remains low until the end of the model.

To complement the probabilistic view, let us explore a geometric perspective, analyzing the latens directly as points in Euclidean space, i.e before mapping them to token probabilities.

Simplistically the task solved by an autoregressive model is that of mapping the input embeddings of the current token to the output embeddings of the next token through incremental modification of the latent d-dimensional vector traveling through the transformer. Geometrically, this latent describes a path through d-dimensional Euclidean space. We set to characterize this path.

Every forward pass of a language model produces, at each position, a latent vector whose dimensionality is fixed by model architecture. At the output end, the model applies a single unembedding matrix , where each row corresponds to a vocabulary token. The logits emerge purely as inner products: . No bias terms or nonlinearities intervene between the final hidden state and the logits.

The effect of this structure is that only directions spanned by the rows of - that is, the token vectors - can influence the logits. This set of directions defines a token sub-space

Algebraically, the token vectors are full-rank, so spans all of , but empirical analysis show that token vector concentrate on a low-dimensional ellipsoid.

This is where things get interesting. We can decompose our latent uniquely as

and means that a computation of our logits can be written as

showing that logits depend only on the component that sists inside the token sub-space; anything in the orthogonal directions is invisible to the language-model head.

This observation allows a clean decomposition. The latent separates uniquely into two orthogonal components: one inside , the other in its complement . The projection onto can be written as , and logits depend solely on the projected part: .

Remember back to our previous discussion on the anatomy of a language model, with the residual stream being a communication channel of low dimensional subspaces.

The logit lens is inherently blind to meanwhile the orthogonal component may be important to the computations carried out by later layers and for predicting the next token in those layers. Crucially the logit lens only sees part of the picture, a projection of the true d-dimensional latent onto a token plane. To qualify this, the authors establish token energy, a measurement which captures how much of 's "energy" translates into logit scores. By analyzing this metric throughout the layers they find that token energy remains relatively low throughout the first 40 layers, then as entropy collapses and the english language probabilities dominate, the token energy increases but only slightly, before spiking on the last 10 layers when the model probalities switch from english to chinese.

What's going on here? Initial probing made it seem like english was used as a pivot language in the models middle layers before finally translating to the desired language. Further analysis shows us something even more interesting. In fact our latent contains very little information of the output tokens. However, probably due to the natural language bias of pretraining, we're slightly biased towards english output tokens. What is actually happening in these middle layers is beyond scope of the paper but we know out latents are carrying a lot of information that is orthogonal to token subspace. Imagine 2 dimensions where the x plane represents output tokens, we can imagine that the our model is freely manipulating the y dimension of this vector, manipulating information as the latent flows through the model. In the early layers there is zero movement along the x-plane and the responding probabilities are 0, as we pass layer 40, the model is still manipulating most of its information in the y dimension, but projected onto x there is now a slight bias towards the english output tokens. Then as we get closer to the final layers, our x dimension shifts and most of our token energy now comes from the x dimension and now near the chinese language tokens.

Do Multilingual LLMs Think In English?

This paper performs three experiments, arguing that models do indeed use English as an intermediary representation, or at least as a strong anchor, even in computation that is completely english-free. Below I briefly present the three experiments, along with my opinionated response to these experiments or how they can actually fit in to a larger existing mental model.

4.1

Prompt the model to generate full sentences in Dutch, French, German and Mandarin and decode every intermediate latent. A broad analysis of the latents, through logit lens, shows that lexical tokens (noun, verbs, pronouns) overwhelmingly appear in their English equivalents first; grammaticl function words rarely do. Semantic decisions are made in a representation region closest to English; whether the input/output language is Dutch or Mandarin is secondary. Degree of routing correlates with pre‑training multilingual diversity and model size.

4.2

Build topic and language steering vectors from parallel corpora. Compare sucess rate when steering non-English prompts with English-derived vectors vs target-language vectors. English steering vectors consistently outperform same‑language vectors at inducing the desired topic and keeping fluency. Steering vectors across languages have high cosine similarity but retain a language‑specific offset. If the concept space were truly universal, steering effectiveness would be language‑agnostic. Superior English steering indicates the latent space is English‑centric, not language‑neutral.

4.3

Use a city facts dataset containing translations of city facts such as "The capital of Canada is .." / "De hoofdstad van Canada is ...". Pinpoint the layers where these facts are stored through causal tracing; then linearly interpolate between the Dutch and English hidden states. Facts localise in the same layers regardless of language. Interpolating hidden states keeps the answer (“Ottawa”) correct while the output language drifts toward English, showing an English decoding bias. Semantic content appears shared across languages (supporting a common fact manifold), but the decoding head pulls outputs toward English, reinforcing the claim that key decisions live in an English‑tilted region.

Relation to "Do Llamas think in English" paper

Despite arguing against Wendler et al I believe that this paper enriches our understanding of the latent representation established before rather than contradicting them. Taken together, the two papers support a unified picture: latent computation happens in a largely language‑agnostic “concept manifold” that is tilted toward English anchors, so the small part of the vector visible to the logit lens often points to English first—especially for lexical content—but the bulk of the vector is still outside the token sub‑space and remains concept‑level. The framework established previously holds under the results of this paper:

-

Latent starts almost orthogonal to .

-

During processing it acquires concept components projection slips into near an English anchor (Phase 2, English logits spike).

-

Final layers translate concept to surface form by sliding the projection within to a target-language anchor (Phase 3, token energy rises; correct token wins).

A response to each section or how to tie it into the overarching framework:

4.1 English content tokens dominate the training data, their output‑embedding vectors saturate the token plane with a dense lattice of “anchors.” During generation the model’s latent state starts mostly outside that plane; as soon as its small token‑aligned slice begins to grow, gradient‑shaped residuals nudge it toward the nearest high‑density region—usually an English content anchor—because that tiny rotation yields the greatest logit boost per unit movement. Only after the concept is stabilised and token energy has risen do later layers pay the extra angular cost of sliding across the plane to a sparser Dutch (or Mandarin) anchor, producing the target‑language word. Function words behave differently: each language’s determiners, prepositions, affixes, etc. form their own dense hubs, so when the network is writing Dutch it can remain in a Dutch island of the token plane and never detour through English. Crucially, this whole English‑first phenomenon concerns the direction of the small visible slice; 70–80 % of the latent norm still lives in the orthogonal concept manifold and is invisible to the logit lens, reminding us to interpret these directional peaks only in tandem with token‑energy magnitude.

4.2 What actually flips the logits is the dot‑product , i.e. the overlap between and the dense web of token anchors. Because English anchors tile the plane much more densely than low‑resource anchors, a vector derived from English sentences inevitably contains a larger and better‑aligned :

- High density ⇒ many anchors with large cosine to ⇒ big logit increase for the desired topic words in any language after the late‑layer rotation to the target surface form.

- Low density (Dutch, Mandarin) ⇒ fewer good matches ⇒ smaller logit shift for the same ‖Δh‖.

Hence an English steering vector can move the projection along a “ridge” of high logit sensitivity, producing a strong topical pull while requiring only a modest perturbation—so fluency is preserved. Steering vectors built in Dutch must push into a sparser region, needing a larger magnitude that disrupts grammatical planning and hurts fluency.

4.3 Again, in accordance with 4.1, this holds under our framework.

How to think about thinking models - Neel Nanda

What is a thinking model? Don't normal models use CoT? What was special about o1? Before o1, CoT had long been estasblished as a way to improve performance of "non-reasoning" models. This goes back even to GPT-3 where you could see reasoning traces appear naturally without prompting. Before o1 this was an artifact of supervised training. Human data will sporadically contain reasoning traces and through supervised training the model learnt to mimic this behavior. o1 however was the first model released that explicitly incorporated reinforcement learning into their training progress which simply gives a reward based on the models ability to solve a problem, today known as Reinforcement Learning from Verifiable Rewards (RLVR). This is a much harder learning problem because it requires exploring the space of possible solutions and it is sparse in the sense where you only get a reward if you correctly solve the problem. However, it has the potential to learn novel strategies. It gives the model a natural incentive to think long and hard about a problem. This opens up a way to shift compute distribution from being all front-end - all compute spent on pretraining and none at inference time - to now having a natural way for models to implicitly learn to think more about problems in relation to how difficult they are to solve.