DeepSeekMath: Pushing the Limits of Mathematical Reasoning in Open Language Models

February 6, 2025.

Late on the ball again... let's see what all the r1 hype is about.

DeepSeekMath presents a large-scale mathematical pretraining dataset and model, structured around dataset curation, supervised fine-tuning (SFT), and reinforcement learning (RL). The paper provides a meticulous breakdown of how the dataset was constructed, why certain architectural choices were made, and how the resulting model performs across key benchmarks.

The dataset is constructed from Common Crawl and refined through a fastText-based classifier, ultimately yielding 120 billion tokens. This is an order of magnitude larger than existing math corpora—7x the size of Minerva’s dataset, 9x OpenWebMath. The data pipeline is designed to maximize relevance and quality, starting with OpenWebMath as a seed corpus and using a classifier trained with 500,000 positive examples from OpenWebMath and 500,000 negative examples from Common Crawl.

Deduplication techniques are employed to reduce noise, trimming Common Crawl down to 40 billion HTML pages. The classifier then selects mathematical content, ranking it by relevance and preserving the highest-scoring entries. The final dataset selection is guided by pretraining experiments, assessing performance at different token thresholds (40B, 80B, 120B, 160B).

DeepSeekMath-Base 7B: Pretraining and Model Structure

DeepSeekMath-Base is initialized with DeepSeek-Coder-Base-v1.5 (a 7B parameter model originally trained for code) and further trained on 500 billion tokens, distributed as follows:

- 56% DeepSeekMath Corpus

- 4% AlgebraicStack

- 10% arXiv

- 20% GitHub code

- 10% Common Crawl (English & Chinese)

Starting from a code-focused base model is a deliberate choice—empirical evidence suggests that models with coding exposure generalize better to mathematical reasoning tasks than those trained purely on natural language. This pretraining setup results in significant gains on GSM8K, MATH, OCW, and SAT benchmarks, while also maintaining strong coding proficiency. Unlike models that degrade in one domain when fine-tuned for another, DeepSeekMath-Base effectively preserves its coding capabilities.

DeepSeekMath-Instruct 7B: Supervised Fine-tuning

To further improve mathematical reasoning, DeepSeekMath-Instruct 7B is fine-tuned with 776,000 instruction-style problems, covering:

- Chain-of-Thought (CoT) for step-by-step reasoning

- Program-of-Thought (PoT) for algorithmic solutions

- Tool-integrated reasoning for leveraging external computational resources

Without tool assistance, DeepSeekMath-Instruct 7B outperforms all open-source models, including Inflection-2, Gemini Pro, and Qwen 72B, surpassing them by at least 9% absolute on the MATH benchmark. Even against proprietary models, it remains competitive, though GPT-4 and Gemini Ultra still hold the lead.

When allowed to incorporate external tools (e.g., symbolic computation, programming), DeepSeekMath-Instruct 7B reaches ~60% accuracy on MATH, establishing itself as the strongest open-source model for mathematical reasoning.

Reinforcement Learning

So far things are pretty standard, a new open dataset -> a better model. Great stuff, and in practice a lot of engineering behind this of course but in theory pretty standard. But now we get to what I've actually been looking forward to in this paper - Group Relative Policy Optimization. However, before we do so, I'd like to provide a quick primer on ppo for those who are unfamiliar.

ppo crash course

Reinforcement learning has long struggled with the challenge of stable and efficient policy optimization. Early policy gradient methods, while theoretically sound, were notorious for their instability—small changes in policy could lead to catastrophic drops in performance, making training unpredictable. Standard approaches, such as vanilla policy gradients, suffered from high variance and lacked a mechanism to prevent overly aggressive updates.

Trust Region Policy Optimization (TRPO) was a big deal when it came out. It tackled one of the biggest problems in reinforcement learning: instability in policy gradient methods. The idea was simple— when the gradient tells us to move in a certain direction, don't trust it fully. The gradient is noisy, it's stochastic in nature, so don't dive head first after it. TRPO enforced this by constraining the KL-divergence between the old and new policies, keeping things stable. By maintaining updates within a "trust region," TRPO significantly improved training reliability, making it a go-to choice for many reinforcement learning applications.

But TRPO had its downsides. It was a second-order method, meaning it required expensive computations, including solving a constrained optimization problem at every update step. This made it computationally intensive and cumbersome to implement in practice. Enter Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO), which asked the same question—how can we take the largest possible policy improvement step while ensuring stability?—but answered it with a much simpler first-order approach. By replacing TRPO’s complex optimization constraints with a clipped objective function, PPO retained stability while being far easier to implement and scale.

At its core, PPO follows a straightforward loop:

- Collect a dataset of trajectories by running the current policy in the environment.

- Score these trajectories using a reward model.

- Compute General Advantage Estimates (GAE) based on the critic’s value function.

- Update the policy using stochastic gradient descent (SGD) and the Adam optimizer, maximizing the PPO-Clip objective.

- Repeat for a long time.

- Profit.

PPO brings two key ingredients to the table: policy optimization and advantage estimation. The synergy between these is what makes PPO work.

- Policy Optimization: The agent collects experience by interacting with the environment. It then updates its policy to maximize expected cumulative reward while ensuring updates stay within a safe range.

- Value Function Estimation: The value function estimates the expected future rewards, helping calculate an advantage signal to guide policy updates.

The PPO-Clip Objective

PPO introduces a clipped objective function to ensure stable updates:

where

is the probability ratio between the new and old policy, and is the estimated advantage.

The function is defined as:

Case 1: Positive Advantage ( )

- The action was better than expected.

- We want to increase the probability of taking this action.

- If , the new policy is already favoring this action.

- Clipping prevents excessive updates in this direction.

Case 2: Negative Advantage ()

- The action was worse than expected.

- We want to decrease its probability.

- If , the policy is already discouraging it.

- Clipping ensures we don’t over-penalize it.

Essentially, PPO encourages beneficial actions while preventing excessive reinforcement and discourages harmful actions without completely suppressing them. This ensures training remains stable. For those new to reinforcement learning (RL), it's important to understand how it differs from supervised learning. In both cases, when an output is correct or receives a positive reward, we can provide a strong signal to the network. However, in supervised learning, even when the model predicts the wrong token during LLM pretraining, we can still provide a rich signal indicating what the correct token should have been. In RL, this kind of direct correction isn't possible. If the model makes a bad move, all we can do is discourage that action in the future—we have no direct way of steering it toward the correct move. This challenge becomes even more pronounced when rewards are sparse, requiring multiple decisions before any feedback is received. The model must determine, through trial and error, which actions contributed to success and which led to failure.

General Advantage Estimation

At this point, you might be wondering—what exactly is "advantage"? Advantage measures how much better an action was compared to the expected value of the state:

where is the expected cumulative reward for taking an action in state , and is the expected cumulative reward of the average action the policy takes in state . Naturally, we can either use the reward for the full trajectory, called Monte-Carlo, which results in a low bias but high variance estimation. Alternatively, we can bootstrap, estimating the value fo future states using a single step lookahead, without waiting for full Monte-Carlo returns:

This is sample efficient but it introduces high bias. General Advantage Estimate (GAE) interpolates between these two approaches, introducing a weighted sum of k-step temporal differences, controlled by hyperparameter , to balance the bias-variance tradeoff. It might sound complicated but we're just calculating the temporal difference at steps and taking the weighted sum of these errors:

where is the temporal difference:

GAE integrates short-term and long-term information, balancing bias and variance in advantage estimation. When , it collapses to one-step TD, relying solely on immediate estimates. When , it becomes Monte Carlo estimation, using full trajectory returns.

To bring this together—GAE determines advantage by observing how the critic network's value estimate evolves over the next steps. A positive advantage means future states are expected to be more valuable, reinforcing the action taken. By blending MC and TD, GAE smooths advantage estimation, reducing variance while keeping bias in check, which helps stabilize PPO training. It effectively combines short-term corrections with long-term trends, ensuring more reliable updates.

If this still feels abstract, consider it this way: we’re looking a few steps ahead, estimating the value at each state, and comparing those values to judge whether the action taken in the initial state was actually beneficial.

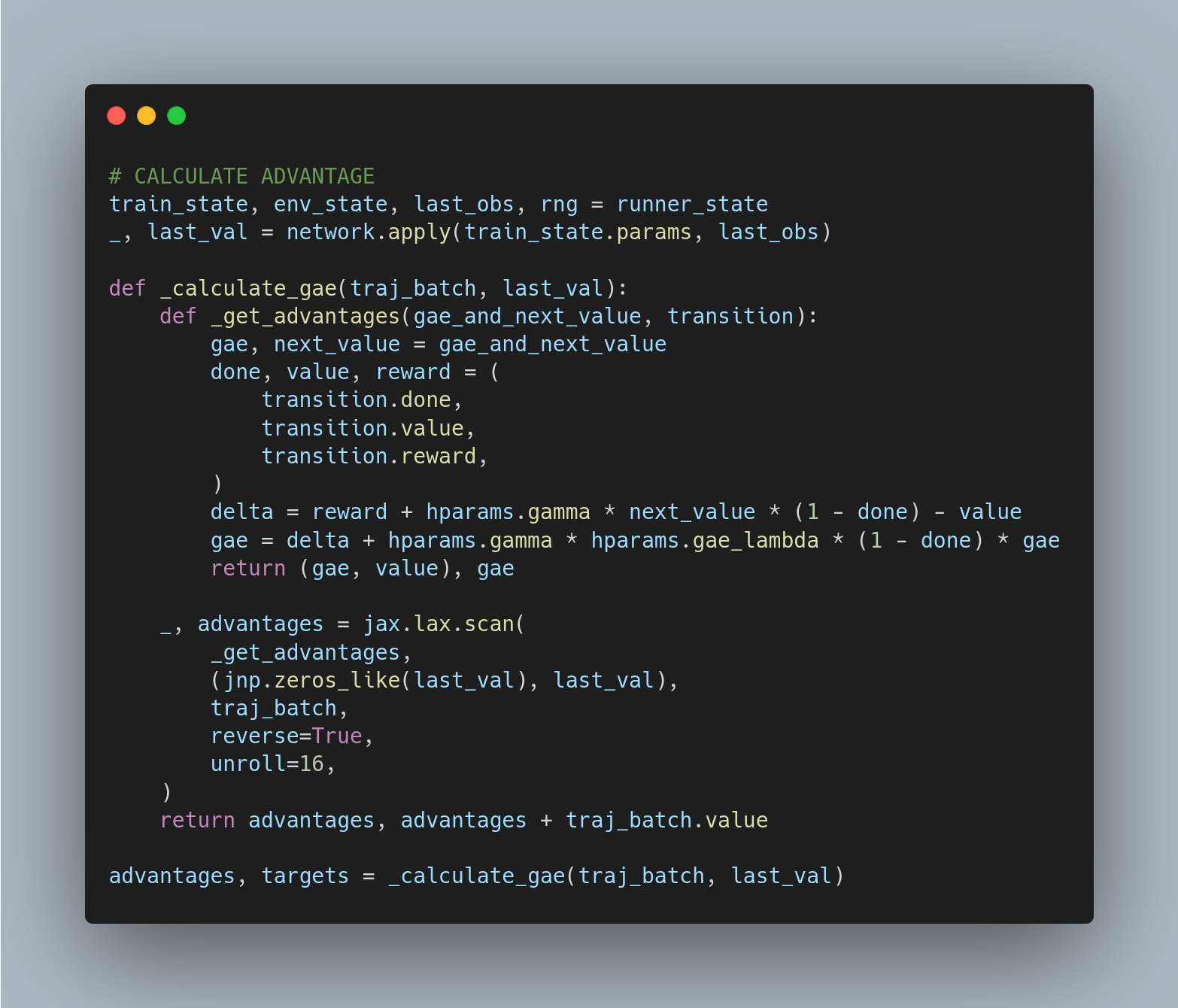

For those who prefer code over formulas

concluding thoughts

PPO works because it updates the policy efficiently while keeping changes constrained. The clipped objective ensures stability, while GAE provides a reliable advantage estimate. A lot of the tricks of PPO boil down simplicity and stability, taking small updates steps within our trusted region with a smooth advantage estimation. If you take one thing away from this, it's that PPO is just doing trust region optimization, but without all the second-order math.

It may not seem natural at first to apply PPO in the context of a language model, but I assure you it hardly requires work.

- Policy : the LLM that has been pre-trained / SFT’ed

- Reward model : a trained and frozen network that provides scalar reward given complete response to a prompt

- Critic (): also known as value function, which is a learnable network that takes in partial response to a prompt and predicts the scalar reward.

This formulation enables the application of PPO on LLMs.

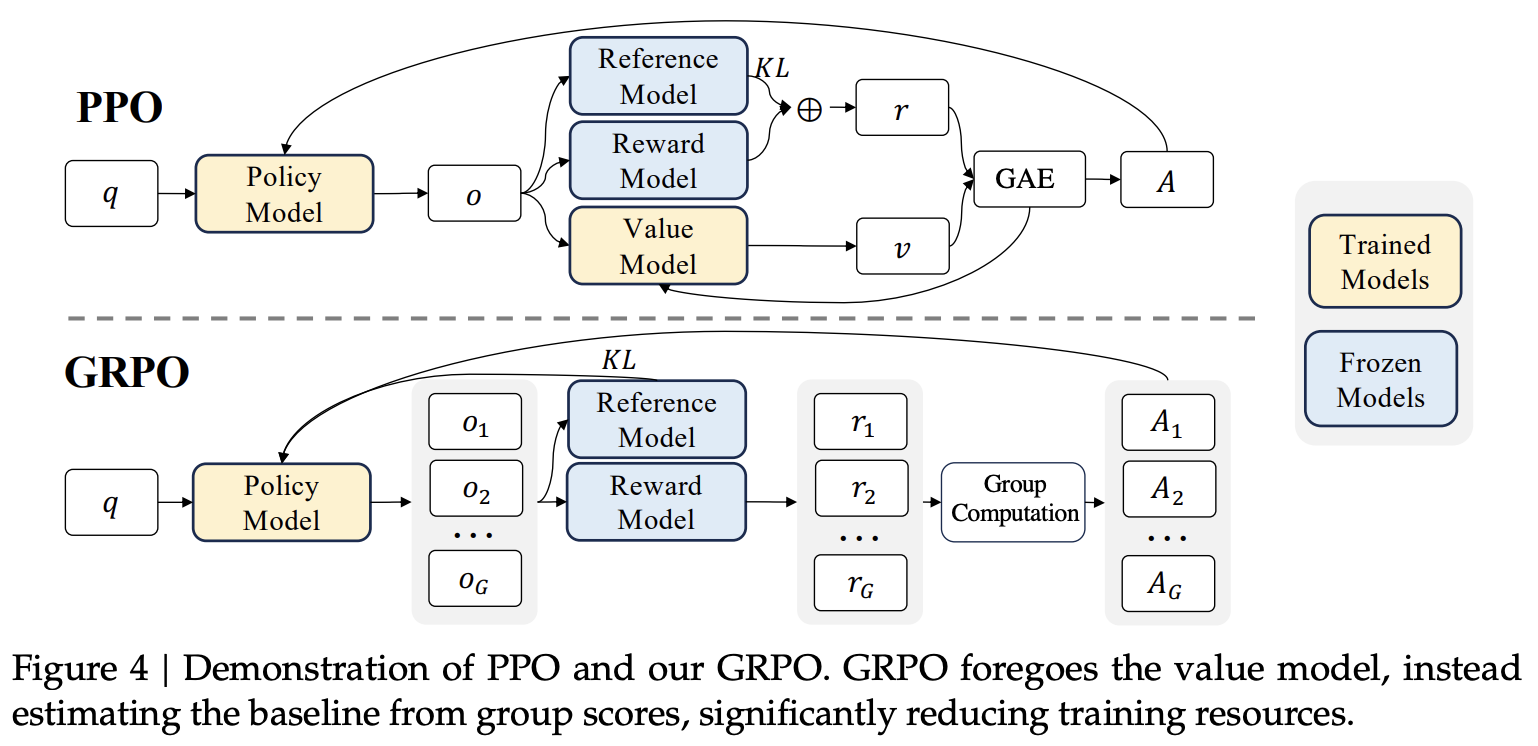

One of the primary downsides of PPO is the requirement to train a value function (or critic network) alongside the policy model. To prevent reward model over-optimization—an issue particularly relevant for LLMs—the standard approach incorporates a per-token KL penalty from a reference model into the reward at each token. Typically, the reference model used for this regularization is the initial SFT model.

Since the value function in PPO is generally a model of comparable size to the policy model, it introduces significant computational and memory overhead. In standard PPO, the value function serves as a baseline for advantage estimation, reducing variance during training. The advantage function quantifies how much better or worse a particular action is compared to expected performance, with the value function playing a stabilizing role in this estimation.

However, reinforcement learning for LLMs diverges from traditional RL settings like robotics or games, where step-wise rewards are assigned at every timestep, allowing straightforward training of a value function to predict future rewards for each action. In contrast, LLM reward models typically produce a single scalar reward for an entire sequence, meaning that only the final token explicitly receives a reward. This creates a fundamental problem: PPO relies on per-token advantage estimates, but the value function has no direct supervision for intermediate tokens. Training a value model under these conditions is inherently unstable, as it must infer the distribution of the final reward across the entire sequence, leading to high variance and unreliable training. The value model struggles to produce meaningful token-wise predictions, degrading advantage estimation quality and increasing training instability.

Trajectory Collection for PPO Requires State-Value Estimates

PPO requires trajectory collection with state-value estimates, which depend on a well-trained value function. However, in the context of LLM training, bootstrapping advantage estimation from intermediate token values is problematic due to the lack of direct token-level reward signals. The need to approximate per-token values from a single sequence-level reward further exacerbates variance and limits training efficiency.

Computational and Memory Overhead

In LLM training, the PPO value network is a separate model, often of similar size to the policy model, significantly increasing computational and memory costs. The additional burden of maintaining and updating a large-scale value network makes PPO resource-intensive, particularly when applied to large transformer-based models.

grpo

to address these issues the authors introduce Group Relative Policy Optimization (GRPO) which obviates the need for additional value function approximation as in PPO, and instead uses the average reward of multiple sampled outputs, produced in response to the same question, as the baseline.

The group relative way that GRPO leverages to calculate the advantages, aligns well with the comparative nature of rewards models, as reward models are typically trained on datasets of comparisons between outputs on the same question.

GRPO modifies the standard Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO) approach by removing the value network and instead estimating the advantage function using group-relative rewards. This makes training more efficient by eliminating the need to compute a value for each policy generation. Instead, advantages are computed after complete outputs are generated, and the loss is then calculated using a per-token advantage.

-

Sample full outputs

Generate completions for each input prompt using the old policy .

-

Compute group-relative rewards

- Each output is scored using a reward model.

- The rewards are normalized within the group:

-

Compute per-token advantage

Unlike PPO, which estimates an advantage at each token step via a value network, GRPO assigns the same normalized final reward to all tokens in an output:

This means advantages are calculated only after full outputs have been generated, not during generation.

-

Compute loss using per-token advantage

The GRPO objective function is defined as:

It is very reminiscent of PPO's objective, albeit with a different advantage calculation. Note how we are summing over both the completions and the output tokens . The KL divergence term regularizes the policy updates.

GRPO introduces a key departure from Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO) by eliminating the need for a value network while still allowing per-token optimization. In PPO, a value network plays a critical role in reinforcement learning fine-tuning (RLHF) by providing expected reward estimates at each token generation step, even though the actual reward is assigned only after the full sequence is produced. The value function helps smooth training by reducing variance in policy gradient estimates, acting as a learned baseline to compare actions against. Instead of relying solely on the final sequence reward, PPO estimates an advantage function at each step, which determines how much better or worse a particular token is relative to the expected return. This allows PPO to compute gradients per token rather than applying a single reward to the entire trajectory, which would otherwise lead to high variance and instability.

GRPO removes the value function entirely and instead replaces it with empirical reward estimates derived from multiple sampled trajectories per prompt. Rather than learning a function to predict expected rewards, GRPO samples a group of outputs for the same input and computes a group-relative reward by normalizing the rewards across the sampled outputs. This group-relative normalization serves as a baseline, replacing the role of the value network in reducing variance. Once this baseline is established, the normalized reward is assigned uniformly to all tokens in the corresponding output sequence, ensuring that each token receives a per-token gradient update.

The core mechanism of GRPO is built on the classic discipline of quality data combined with scale, and under these conditions it becomes sufficient to compare multiple completions against each other rather than learning an explicit per-token value function**. By ranking generated outputs within a sampled batch, GRPO establishes a relative measure of output quality without needing to estimate expected future rewards for every token. This approach simplifies training, making it more computationally efficient by eliminating the need for a separate value network, which typically requires as much memory as the policy model itself.

Overall it raises several interesting questions. First, how well does GRPO scale as models become larger? Does the number of sampled trajectories per prompt need to increase to maintain stable training, or does the method naturally generalize across different scales? Second, could there be a hybrid approach that combines GRPO’s group-based ranking with some form of per-token variance reduction? For example, what if we applied group-relative normalization for reward estimation but still allowed a small value network to guide per-token learning?

ablations and empirical studies

Math - Code transfer effects

Pretraining on code improves mathematical reasoning, even without tool use. However, mixing code and math tokens in a single-stage training process leads to a degradation in mathematical reasoning performance. One possible explanation is that DeepSeek-LLM 1.3B, due to its limited scale, lacks the capacity to fully assimilate both domains simultaneously. This suggests that for smaller models, separate pretraining stages or specialized architectures may be necessary to maximize generalization across code and mathematics.

Pretraining on arXiv for mathematical reasoning

ArXiv papers are commonly included in math-focused pretraining datasets (Azerbayev et al., 2023; Lewkowycz et al., 2022a; Polu & Sutskever, 2020; Wang et al., 2023c), yet their direct impact on mathematical reasoning remains largely unexplored. Experimental results indicate that, contrary to expectations, arXiv data does not significantly improve mathematical reasoning performance.

Models trained exclusively on an arXiv-based corpus show no notable improvement or degradation across the mathematical benchmarks used in this study. However, this conclusion is tentative and subject to several limitations:

- The effect of arXiv data on specific mathematical tasks not included in this study remains unknown. For instance, tasks such as informalizing theorems—converting formal statements or proofs into more intuitive representations—could still benefit from arXiv pretraining.

- The interaction between arXiv data and other pretraining sources has not been explored. It is possible that arXiv papers contribute in a complementary way when combined with other mathematical corpora.

- The impact of arXiv data at larger model scales remains uncertain. It is plausible that higher-capacity models might leverage arXiv information more effectively than smaller architectures.

Pass@K vs. Maj@K

In evaluating mathematical reasoning ability, Pass@K and Maj@K serve distinct roles:

- Pass@K measures whether the model can generate at least one correct answer within K sampled responses. A model that sporadically generates the correct solution but frequently fails will still achieve a high Pass@K score.

- Maj@K measures whether the correct answer appears consistently across multiple samples—i.e., whether the majority of responses among K attempts are correct. A model with high Maj@K rarely produces incorrect outputs, meaning it has been aligned to consistently favor the right answers.

These metrics reveal an important trend: RL fine-tuning generally increases Maj@K but does not improve Pass@K. This suggests that RL is not teaching the model new reasoning skills but is instead adjusting its probability distribution to make correct answers more frequent.

If the model already has the knowledge required to solve a problem but occasionally produces incorrect outputs, RL fine-tuning reweights its distribution to favor the correct response more consistently. However, if the model was never capable of solving the problem to begin with, RL does not help—it cannot create new knowledge, only optimize existing behavior.

This insight is critical in understanding the role of RLHF (Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback) in LLMs: it does not improve raw problem-solving ability but instead aligns outputs to be more reliable and human-preferred.