Physics of Language Models

September 19, 2024

Physics of Language Models is a collection of papers that aim to understand how Language models work. In their own words: "Our goal is to establish universal laws for LLMs that can guide us and provide practical suggestions on how we can ultimately achieve AGI.".

Even today, GPT-4 and Llama-3 still provide incorrect answers to some questions that are simple for humans. Is this a problem inherent to GPT-4, or is it due to insufficient training? Is its mathematical capability too weak? Does this only affect models as of July 2024, or will GPT-6 and Llama-5 also face this problem? What about other pre-trained models?

To quote the authors:

We propose dividing the concept of "intelligence" into multiple dimensions (such as structures, knowledge, reasoning, etc.). For each dimension, we create synthetic data and build an idealized environment for LLM training to understand the theory and push the capability of LLMs in this dimension to the extreme. By performing a large number of controlled experiments, we aim to discover the universal laws of all LLMs, not just a particular version of GPT-4.

The study is in three parts: Part 1 - Structures, Part 2 - Reasoning, and Part 3 - Knowledge. Each part is studied individually, the process can be broken down into:

- Decompose intelligence into building blocks (structures, knowledge, reasoning), and study them individually

- Build synthetic datasets that enable study in controlled, idealized environments. This allows you to tweak parameters such as difficulty, amount, distribution, and evaluate how these things effect model performance. Allows you to make informed decisions on how to train future models

- Highly repeatable experiments. Use smaller models (100M size), where you can run feasible, repetitive experiments, in an attempt to derive universal laws.

- Probing techniques to see the inner workings of models.

Part 1

not covered

Part 2

How do Language Models reason? Well, people would argue that they don't, but that discussion is of little interest to me, instead, let's assume they can reason and try to uncover how they do so. The authors set out to uncover the hidden reasoning processes of language models when solving grade-school math problems. Their goal was to understand the fundamental mental processes these models develop and why they sometimes stumble on seemingly simple problems.

To investigate this, the researchers create iGSM - an infinite, synthetic dataset similar to GSM8k. This dataset captures various types of dependencies:

- Direct dependency (e.g., A = 5 * (X + Y))

- Instance dependency (e.g., X classrooms each has Y messenger bags)

- Implicit dependency (e.g., Bob has 3x more fruits than Alice. Alice has 3 apples, 4 eggs and 2 bananas)

What makes iGSM particularly powerful is its diversity. The framework ensures incredibly diverse problems, with over 90 trillion solution templates - far more than a model like GPT2-small (100M parameters) could simply memorize. This vast problem space sets the stage for a deep dive into language model reasoning.

Part 2.1: Grade-School Math and the Hidden Reasoning Process

With iGSM in hand, the researchers began their investigation. The problems in this dataset require multiple reasoning steps, where the solution sentence describes the necessary steps towards solving the given problem - following a topological order:

(Solution - Easy)

Define Dance Studio’s School Daypack as p; so p = 17.

Define Film Studio’s Messenger Backpack as W; so W = 13.

Define Central High’s Film Studio as B; so B = p + W = 17 + 13 = 7.

Define Film Studio’s School Daypack as g; R = W + B = 13 + 7 = 20; so g = 12 + R = 12 + 20 = 9.

Define Film Studio’s Backpack as w; so w = g + W = 9 + 13 = 22.

Define Central High’s Backpack as c; so c = B * w = 7 * 22 = 16.

Answer: 16.

To avoid errors from large number computations, arithmetic is performed modulo 23. Two datasets are created:

- iGSM-med: problems requiring up to 15 operations

- iGSM-hard: problems requiring up to 21 operations

and are used to pretrain small language models from scratch, in this case the chosen architecture is GPT-2 (with rotary embeddings) with ~100M parameters. Surprisingly, models trained on iGSM-med achieved >85% accuracy on problems up to 22 operations, while those trained on iGSM-hard maintained >80% accuracy up to 32 operations. This unexpected performance led to a significant result:

Result: GPT2 performs well when pretrained using iGSM-med or iGSM-hard data, even when evaluated out-of-distribution on harder (i.e., larger op) math problems. Thus, the model can truly learn some reasoning skill instead of memorizing solution templates.

These are exciting results, but how exactly are models solving these problems? The researchers propose that GPT-2 achieves "level-1" reasoning skills, using topological sort and providing the shortest possible CoT. This implies something quite remarkable - before generating any output, the model must understand which parameters are necessary for the solution, a non-trivial mental process.

To investigate further, the researchers introduced three probing tasks:

- nece(A): Is parameter A necessary for computing the answer?

- dep(A, B): Is parameter A recursively dependent on B given the problem statement?

- can_next(A): Can A be computed in the next solution sentence?

Remarkably, the models achieved 99% accuracy on these probing tasks, demonstrating a complete understanding of parameter dependencies, necessity, and computation order. This sheds light on the model's internal reasoning process.

The researchers also found that model errors correlate with these probing tasks. For instance, when the model incorrectly calculates nece(A), it often generates the unnecessary parameter A in the solution. Similarly, can_next(A) probe failures lead to premature parameter calculations. This observation led to two important results:

Result: Many reasoning mistakes made by the language model are systematic, stemming from errors in its mental process, not merely random from the generation process.

Result: Some of the model's mistakes can be discovered by probing its inner states even before the model opens its mouth (i.e., before it says the first solution step).

As the researchers dug deeper, they uncovered another fascinating aspect of language model reasoning - the relationship between a model's depth and its reasoning length. Through a controlled study of different model widths and depths, they arrived at another significant result:

Result: Language model depth is crucial for mathematical reasoning.

This may contradict previous findings suggesting that size is the important scaling parameter, regardless of whether you scale width or depth. The researchers looked at the nece(A) probing task, focusing on necessary parameters at distance t from the query parameter. They found that deeper layers are significantly better at predicting parameters further away from the query, while shallow layers excel at parameters close to the query. This led to a crucial insight:

Result: The depth of a language model is crucial, likely due to the complexity of its hidden (mental) reasoning processes. A t-step mental reasoning, such as mentally computing nece(A) for parameters A that are a distance t from the query, may require deeper models for larger t, assuming all other hyperparameters remain constant.

Part 2.2: Learning from Mistakes on Grade-School Math Problems

With a better understanding of how language models reason, the researchers turned their attention to a practical question: how can we improve model performance on these math problems? They found that models trained on correct data can act as verifiers, detecting their own mistakes. However, simply allowing the model to backspace and retry only yielded modest improvements (~2 percentage points).

To enable true learning from mistakes, the researchers introduced "retry data" - training data containing intentional mistakes followed by corrections. They experimented with different probabilities (p) of including these mistakes, ranging from 0.01 to 0.5. The retry data included a special [BACK] token to indicate a correction:

Define Film Studio's School Daypack as [BACK].

To ensure fair comparisons, the researchers conducted controlled experiments. Models trained with retry data saw the same number of tokens as in the error-free case. Interestingly, this meant that models trained with retry data actually saw fewer math problems overall, especially for larger values of p.

The results were astounding. Models trained on retry data showed immense performance improvements, with higher p values yielding better results. For example:

- On iGSM-med (op=23), accuracy jumped from 78% to 95% with p=0.5

- On iGSM-hard (op=32), accuracy improved from 84% to 96% with p=0.5

This led to a counterintuitive result:

Result: Within a reasonable range, the more mistakes the better. Especially on hard problems, such as on iGSM-med op=23, the accuracy jumps from 78% to 94% by using retry rate = 0.5.

Surprisingly, models trained on fewer problems with more mistakes performed better. Moreover, these models hardly resorted to retrying during inference, unless the retry rate was very high:

Result: Models pretrained on retry data hardly retry (unless retry rate is very high).

This finding has significant implications for training language models. It suggests that it's actually very safe to include math data with mistakes and corrections in your pretrain data. Generally, the more mistakes + corrections, the better. Remarkably, it does not interfere with either the pretrain or the inference process!

There is however an important caveat: error correction must be instilled during pretraining. Unlike error detection, it cannot be effectively learned through fine-tuning:

Result: Error correction is a skill that can be fundamentally different from beam search or retry based on the model's randomness.

Part 3

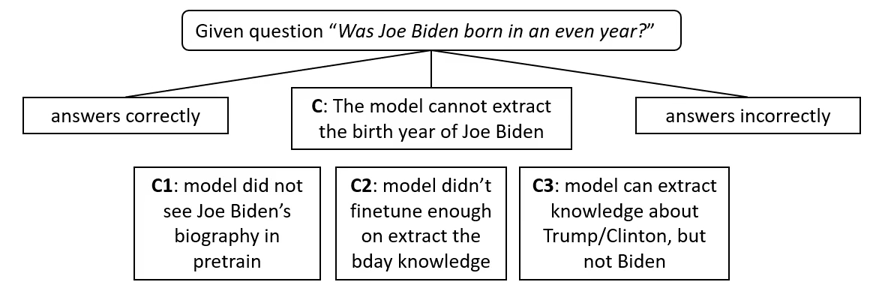

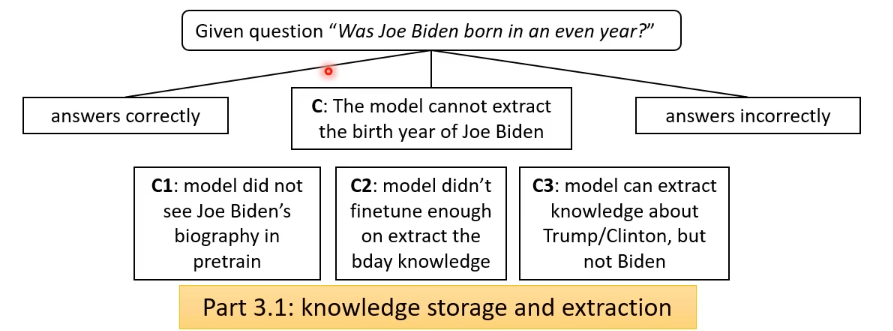

How do Language Models store knowledge? Back in November 2023, the authors asked GPT-4 a simple question "Was Joe Biden born in an odd year?" to which it answered Yes. This is of course wrong as Biden was born in 1942. Why does this happen? We can break do down as such

Part 3.1 Knowledge Storage and Extraction

If we assume that the model has seen Joe Biden's birth year during pretraining, then we can ask ourself why it is not able to extract this information at test time. That is exactly what part 3.1 aims to understand: understand under what conditions language models can extract information that it has seen in its pretraining data.

Designed a synthetic dataset of biographical data of N individuals, called the BIO dataset, listing information on 6 attributes name, birthdate, education, employment, living locations, etc in varied sentences.

"Anya Briar Forger was born on October 2, 1996. She spent her early years in Princeton, NJ. She received mentorship and guidance from faculty members at Massachusetts Institute of Technology. She completed her education with a focus on Communications. She had a professional role at Meta Platforms. She was employed in Menlo Park, CA."

Paired with these biographies, they design a Q/A dataset, constituting 6 questions per individual. Each question is used as a prompt for the model to generate a response. This dataset is split into a train and test set, such that one can truly evaluate memorization: the model has seen the answer during training extraction: the model is able to extract the answer to the question from the BIO.

The model is trained from scratch, and the BIO data is always a part of this pretraining dataset. Sentences are concatenated into 512 token sequences, separated by a standard

Now we've got the setup ready, this is what the authors use to examine the aforementioned question: under what conditions are language models able to extract information that it has been pre-trained on. Remember that the BIO data is always a part of the pretraining data, so the answers are all there.

Mixed-Training. BIO and Q/A (only the train half) data is randomly sampled and trained from scratch. Under these conditions, the language model is able to accurately answer 86.6% of the test set QAs. Hence, Mixed-Training -> Knowledge extraction

BIO Pretrain + QA Finetune. Mixed-training is however not akin to how language models are typically trained. Rather, models are pretrained on randomly structured corpus of web data, and then instruction tuned. To mimic this, the authors pretrain a model on the BIO data and then finetune on the QA data, both full fine tuning and LoRA. Despite a 99% accuracy on both the pretrain and the finetune datasets, the model is unable to generalize out of distribution to the test set QAs. This is a universal law, independant of architecture, size, training parameters etc:

Rule: A model pretrained to word-by-word memorize knowledge may never be fine-tuned to extract knowledge. Perfect BIO token memorization + perfect QA answers for half the people != correct QA answers for the other half.

This comes as a shock to me. And it did for the authors as well, until they realized that there is only one biography per person. What happens if we augment the BIO dataset such that knowledge is mentioned multiple times using sentence diversity, permutation, translation, writing styles? Well... the test accuracy jumps to 96%! So, it's absolutely necessary to augment the pretrain data for knowledge extraction. But, why?

To answer this question the authors probe the models, in what they call position-based probing (P-probing). They identify six special token positions immediately preceding the first occurrences of the six attributes in each biograph entry:

"Anya Briar Forger was born on October 2, 1996. She spent her early years in Princeton, NJ. She received mentorship and guidance from faculty members at Massachusetts Institute of Technology. She completed her education with a focus on Communications. She had a professional role at Meta Platforms. She was employed in Menlo Park, CA."

Using the hidden state of the last hidden layer at each of these token positions, the authors train a linear classifier to predict the target attributes. Without knowledge augmentation, the P-probing accuracy is close to 0% until the token immediately preceding the target attribute. The authors posit that this happens because the model learns the wrong logic: someone born on Oct 2, 1996 in Princeton and studied Communications at MIT works for Meta. Rather than learning the right logic: Anya works for Meta. When knowledge augmentation is applied, given that the connection of Anya -> Meta is seen multiple times, in multiple permutations, the model does store this (key, value) correctly. The P-probing supports this, and supports a claim even stronger actually: the accuracy for all six attributes rises to nearly 100% from the first special position, meaning before all of the attributes! This indicates that the model not only memorizes the BIO data but also identifies the person's complete six attributes solely upon seeing the person's name, facilitating knowledge extraction during the QA finetuning process.

Rule: Adding multiplicity, permutations, or repeating full names, all help the model to better store knowledge during pretraining, making knowledge extraction easier later.

In practice, it's not feasible to augment data for all individuals. And you'll most likely find that some individuals appear in several instances in the data, and others only appear once. To explore the effects of this on the model, the authors devise an experiment of N minorities without knowledge augmentation (1 entry), and M celebrities with knowledge augmentation (5 entries). The model is pretrained on the BIO data (N + M), and finetuned on M/2 QAs. According to our previous knowledge, the performance on test celebrities should be high, because we applied knowledge augmentation to the celebrities and half the QAs are in the finetuning data, and the performance of minorities should be bad, because they are not augmented, and are not in the finetune data. But what actually happens is that we get 80% accuracy on the N minority QAs! Wow! It turns out that by mere existence of knowledge augmented individuals in the pretraining data, the model learns how to store knowledge in a format that enables knowledge extraction.

Rule: Introducing celebrity data boosts the minority group’s QA accuracy (e.g., from 4.4% to 86.8% for the bioS data).

Part 3.2 Knowledge Manipulation

Knowledge Manipulation assumes that knowledge is fully extractable, as explored in Part 3.1, and now you instead want to study the skills of language models to manipulate the knowledge. For example, can they answer questions such as "Was Joe biden born in an odd year?" or "Was Donald Trump born earlier than Nancy Pelosi?" based on their memorization of celebrities' birthdays? The authors are interested in questions that are functions of extracted knowledge from the pretraining data. The functions explored in this study are simple forms of logical reasoning, as exemplified earlier: "Is X born in an odd year?", "Was A born in a southern city?" etc.

To test this, the authors pretrain a model on the BIO data of N individuals, then they finetune or pretrain on knowledge extraction of all N individuals (this is the same as QA finetune from 3.1), and finally they finetune on knowledge classification on N/2 individuals. Classification finetuning here means finetuning on examples of manipulation, with and without CoT:

"Q: Was Anya Briar Forger born in an even month? A (without CoT): Yes. A (with CoT): October, so it is Yes."

This setup should look familiar because its the same premise as in 3.1, pretrain on the prerequisite knowledge, finetune on half the examples of the task you want to evaluate, then evaluate on the other half.

So, what happens when we evaluate the model ability to classify the remaining N/2 individuals? When the model is prompted to use CoT, it has a 100% accuracy, but (!) without CoT, the accuracy is no better than random guessing: 50%?? What this means is that the authors discover that knowledge manipulation, even in its simplest form, single-step, is impossible without CoT. This applies for other manipulation tasks, ranking, comparison etc. Despite the inclusion of CoT at training time, the model can not manipulate knowledge without first writing it out explicitly (CoT) at inference time. Now, please note that this is different from CoT in reasoning, GPT-4 is very capable of answering what the sum of A and B are without writing down A+B explicitly, but when it comes to manipulating extracted knowledge, it has to write down the knowledge before manipulating it.

Even though these laws are established on experimental models, these rules did apply even to the best and brigtest LLMs (at least as of July 2024). Asking GPT-4 to classify birth months of celebrities it has 50.7% accuracy, asking it to rank birth dates it has 52.3% accuracy.

Part 3.3 Knowledge Capacity Scaling Laws

Scaling Laws are a pivotal area of research in large language models as they enable predictions about the performance through experiments with smaller ones. In the training regime there are established models for these scaling laws, discussing the optimal training flops versus model size. However, there is a lack of research in trying to understand what the ultimate performance that a model is capable of achieving, assuming sufficient training. This study aims to understand scaling laws of knowledge capacity, that is, estimating the number of knowledge bits a model stores, with a focus on factual knowledge representation as tuples, such as (USA, capital, Washington D.C).

So what do we mean with a knowledge bit?

Let's imagine creating a synthetic English dataset describing knowledge tuples, and creating our first entry:

- (Anya, birthday, 10/2/1996)

Well if these birthdates are uniformly drawn from any day, of any month, in the past 200 years, then this represents bits of knowledge. So going back to the BIO data consisting of N biographies, we can actually estimate the amount of information that is present, and that is regardless of how the biographies are written, and how many times they are repeated. Now, in the paper they introduce a new synthetic dataset that has even more tunable hyperparameters than just N biographies but I'm not going to detail this because the logic is the same: for any time of synthetic knowledge, the authors propose a formula to compute the knowledge bits stored in this dataset.

Now suppose we pretrain a LLM on your synthetic dataset, we can actually compute the amount of learned knowledge (in bits) of our models. However, doing so it not trivial. If the model achieves 0 loss on the dataset, then obviously the model has fully captured the knowledge, but what if the model is 50% accurate? Well in that case you need to be more careful in how many bits you say that the model stores.

The authors posit that for a wide range of model sizes/depths / widths (i.e. only size matters):

LLM can "consistently" achieve 2bit/param in storing knowledge if sufficiently pretrained

sufficiently trained but what does sufficiently trained mean? It means that the language model has to be exposed to the knowledge (think knowledge tuple from before) 1000 times. This doesn't necessarily mean that you have to pass over every piece of knowledge 1000 times, but rather that you have to see the tuple, in some constellation (different writing styles are ok), 1000 times.

but what if there are less exposures? Well then GPT-2 consistently achieves 1bit/param, but even more interesting is that at 100 exposures then the architectures start to matter! In the 100-exposure setting, some architectures are worse in knowledge capacity: e.g., LlaMA / Mistral architectures can be 1.3x worse than GPT. Don't forget that we're talking about the knowledge capacity of these architectures, and specifically knowledge capacity for rare knowledge. Controlled experiments by the authors find why this is the case, there are in total 7 architectural differences between GPT-2 and LLaMA, and by turning each one of these on and off they find that its the MLP layer that causes this difference. Replacing the GatedMLP layer of LLaMA / Mistral with vanilla MLP, then the knowledge capacity improves to that of GPT-2 at 1bit/param.

Good vs Junk But in practice, your dataset is not only going to contain "good data", in the sense that not all data is going to contain knowledge. Your going to have a lot of junk data. So what happens to our knowledge capacity in the case where a model is pretrained on a mix of junk and good data? The authors investigate the case of 1/8 tokens good data and 7/8 tokens junk. Overall the authors find that "junk" data significantly harm LLM's knowledge capacity on good data. When the good data is exposed 100 times, the capacity ratio may degrade by 20x compared to the baseline of no junk. Even trained on 300/600/1000 exposures, the capacity still degrades by 3x/1.5x/1.3x. The junk data here is defined as BIO with an extremely high N value. In contrast, if the junk data BIO(N') has a very small N, simulating highly repetitive knowledge s (e.g., “da Vinci painted the Mona Lisa” in millions of variations) it may not effect the model's capacity for standard knowledge.

Why 1/8 split of good data? I'm assuming what they mean here is that 1/8 of the data is exposed 100 times, and that is what we're trying to make the model learn, and then the rest 7/8ths is random pieces of knowledge, less structured, and only exposed 1 time. In this case we want to see how well the model is able to store the knowledge exposes multiple times.

There is however a suprising fix to this, by just appending the domain name (e.g. "wikipedia.org") at the front of all pretrain data paragraphs, LLMs learn which domains are rich in high-quality knowledge and prioritize learning from them. This is an amazing result that I would love to dive further into.

Quantization. All models are trained in mixed precision. What happens when models are quantized to int8 / int4 post training? It turns out that quantizing to 8 bits has negligible impact on their capacity! Thus, even for models at peak capacity of 2bit/param, quantizing to int8 does not effect capacity. This means that language models are capable of a 4:1 compression ratio. This can be compared to zip which is roughly 100:1. Large language models are super good at compressing knowledge.