maximize gpu utilization

August 29, 2024

i read two posts [1, 2] which led to some notes, which led to this post.

Most people are resource-constrained, and even those who aren't still need to utilize their resources effectively. Optimizing deep learning systems is therefore crucial, especially as models grow larger and more complex. To do this effectively, we need to understand the kinds of constraints that our system may suffer under, and how these constraints interact with different aspects of model architecture and training pipelines.

Typically, the accelerator of choice here is a GPU, and I'll use GPU as an all-encompassing term for accelerators like LPU, TPU, etc. On a GPU performing deep learning, your time is split between three components:

- Compute - The time spent performing operations (FLOPS).

- Memory - The time spent moving data (tensors) between different layers of the GPU.

- Overhead - Everything else.

Understanding which of these you're capped in will make optimizing your system both easier and more effective. You can improve the speed of your search algorithm all you want, but if you're in the memory-bound regime, the end result is going to be a lackluster performance improvement. So, if you want to improve the performance of any system, you'll need to spend time understanding these regimes, how they work, and when you're in them.

Compute

Compute is the most important regime to utilize effectively. Why? Because it's the fastest, and you have the most of it. So how do we maximize compute? Well, it's usually just spending less time doing other stuff.

Think of your system like a kitchen: your chef (compute) uses ingredients to prepare a dish, and he does so with incredible speed. Your line cook supplies the chef with ingredients. If you upgrade your chef such that he now works twice as fast, it won't matter if your ingredients are still coming out at the same pace as before.

GPUs really want to just burn through matrix multiplications; they've even got specialized compute cores just for that reason. So the more you get them doing matrix multiplications, the better. The reason for this is simple: other operations just don't make up enough of the total time to be worth optimizing for.

Bandwidth

Bandwidth is the cost of moving data from A to B. Movement is hierarchical; one can move data between the CPU and the GPU, between two nodes, or from disk to CPU. These are larger movements, but there is also movement of data within the GPU. When you write nvidia-smi in your console, or when you're complaining about an OOM message from CUDA, you're talking about DRAM. DRAM is the large container(s) that a line cook will fill with chopped ingredients, ready to be transferred into the much smaller and much faster SRAM. The cost of this data movement is what's called memory bandwidth cost. Every time you perform an operation, known as a GPU kernel, you need to move your data from DRAM to SRAM.

If the movement bandwidth cost is higher than the cost of executing the kernel, then your operation is memory-bound. Examples of this are unary operations like torch.cos and torch.log. Such operations scattered inside your code increase memory bandwidth and decrease compute utilization. What can you do about it?

Fusing unary operations, or unary operations with many other operations for that matter, reduces memory bandwidth and allows the data to remain in SRAM while multiple operations are performed in sequence, as a single "fused" operation. This is why writing CUDA kernels is so useful; you can't avoid this memory movement without a specific CUDA kernel written for the operations you want to fuse. GPU compilers such as XLA will try to fuse as much as possible, but automated fusing isn't as good (yet) as a competent human. So... learn CUDA I guess.

Overhead

This is accumulated time spent doing things that aren't moving data or executing kernels. Python type checking, PyTorch dispatcher, launching CUDA kernels – these are all overheads. Now you might think this overhead contributes only to a small part of execution, but remember that your GPU is crazy fast, performing trillions of operations per second. So unless you're working with a large amount of data, your overhead is likely a considerable part of your execution time, because Python is slow.

As long as your GPU operations are big enough, your ML framework will be able to queue the operations while it continues to perform CPU operations. This is called asynchronous execution, and it means that if your GPU operations are large in comparison to your CPU operations, then the CPU overhead is irrelevant. If this is not the case, you should consider scaling the data usage. Overhead doesn't scale with the problem size, while compute and memory do, so if you've got a batch size, double it, and if your runtime doesn't increase proportionally, you're in the overhead-bound regime! For example, if doubling your batch size from 32 to 64 only increases your training time by 20%, you're likely overhead-bound and could benefit from further increasing your batch size.

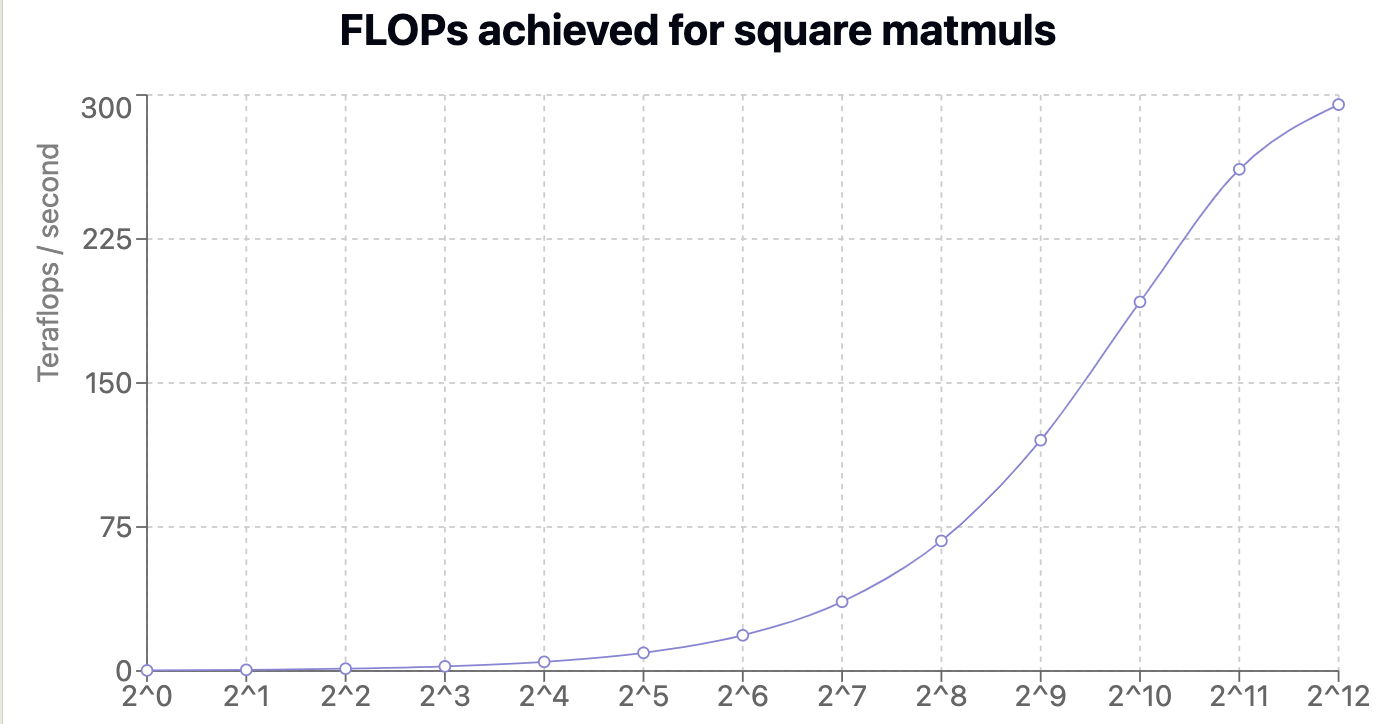

You can see this in action when looking at the teraflops achieved during square matmuls.

As we increase compute intensity, the constant overhead (launching SMs, identifying kernel) is amortized away.

Torch - trying to be everything

Now, why does PyTorch even have this kind of overhead to begin with? Well, there's a pretty natural trade-off between overhead and flexibility. If you want your framework to lend itself to a greater mass of problems, then you're going to have to trade some overhead to enable this flexibility. Now, while PyTorch sells itself with words such as production ready and distributed training [1], I would argue that the reason to use PyTorch in the first place is flexibility. PyTorch is going to work for a lot of cases; it's a safe bet to approach the problem in PyTorch because it's likely got the tools for you. But with the exuberant growth in compute demands we've seen over the past 3 years, I would like to argue that the clean, flexible, debuggable philosophy of PyTorch is quickly becoming a problem.

It's hard to combine flexibility with performance, and their commitment to trying to achieve both is leading the project to a state of fragmented tools that are impossible to use without hours of dev time being sunk into them to try and disentangle it. To me, JAX is the unequivocally preferred solution to this problem. JAX commits to being a compiler-centric framework, through and through. This imposes requirements on the user, such as functions being pure, which requires a mind shift for most new users, but in the end, it leads to such an immense improvement in abstractions that the trade-off is evident. The benefit? Your code will inherently scale and parallelize thanks to the ingenuity of XLA. The compiler will abstract away all the heavy lifting of auto-parallelization, sharding, and scheduling. Scaling across a node, or even multiple nodes, has never been easier. As long as your code obeys the basic JAX restrictions, @jax.jit makes the code available to XLA, which does things automatically for you. When you're past the first hurdle, JAX just makes sense.

I also prefer the functional API approach of JAX to that of PyTorch (even though you can use torch.functional, but have fun with that). It makes the abstractions so much clearer and does away with a lot of anti-patterns that frequently occur in PyTorch code. It aligns beautifully with the nature of scientific computing; scientific computing is built on mathematical functions - pure, deterministic operations that map inputs to outputs without side effects. Neural networks are static composed functions, and therefore writing them in JAX makes a lot of sense. A great example of this is the optax API.

optimizer = optax.adam(1e-2)

This is the definition of an Adam optimizer. Simple, but nothing special. The beauty comes when I'd like to combine Adam with a clipping function. Because of the functional philosophy, I can just compose Adam with the clip function into what Optax calls a chain.

optimiser = optax.chain(

optax.clip(1.0),

optax.adam(1e-2),

)

It just makes sense. I want to apply a clip function followed by Adam. Their original blog posts cover a lot more great examples. I highly recommend the read.