the bitter transformer lesson

July 24, 2024

Richard Sutton's The Bitter Lesson is a fantastic piece that I highly recommend you read. He posits that progress in AI research over the past 70 years fundamentally boils down to two principles:

- Develop general methods, discarding assumptions and attempts at modeling intelligence.

- Leverage computation by scaling data and compute resources.

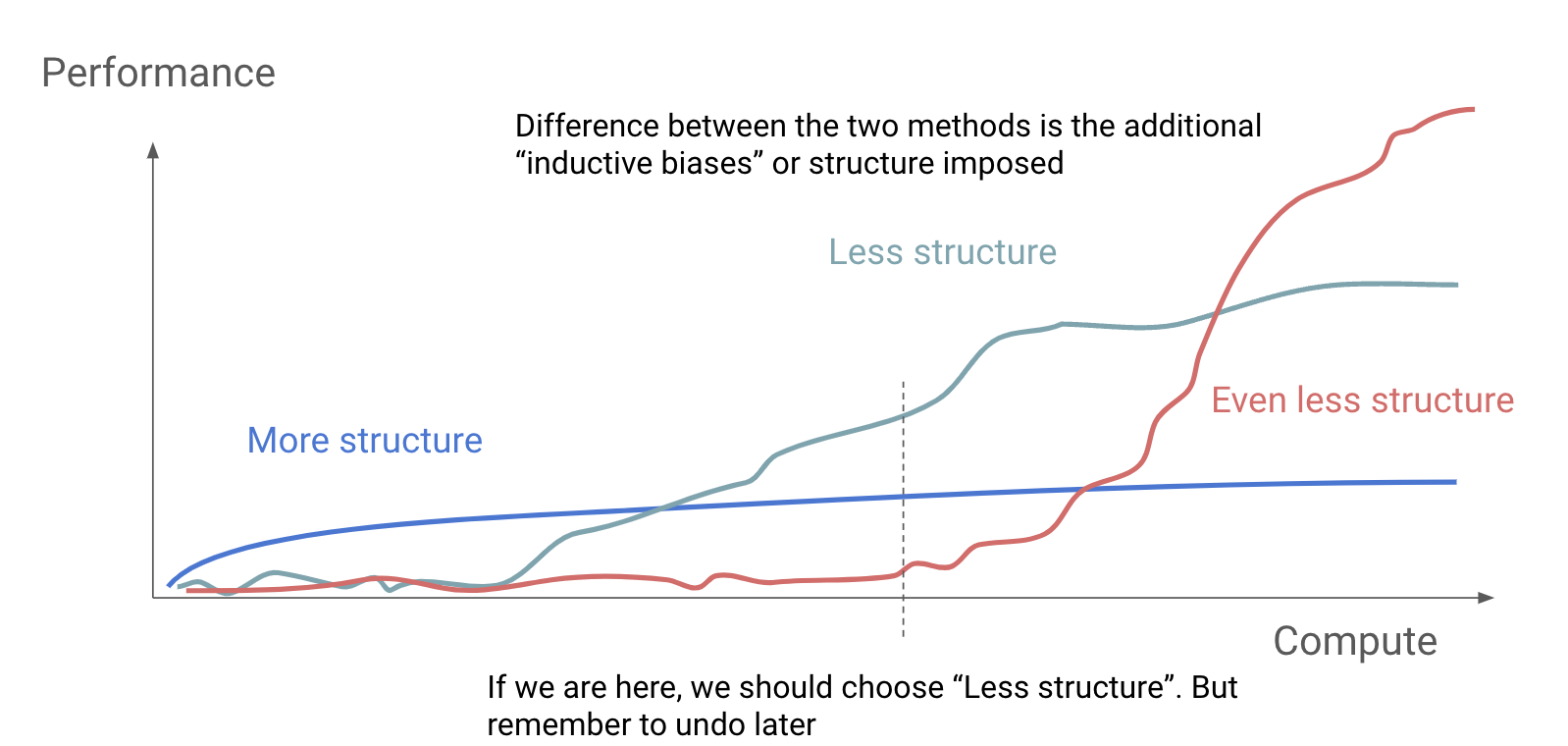

This approach has proven successful across prominent ML fields, including computer vision, reinforcement learning, and speech recognition. The latest example is the astounding progress in NLP. As available compute increases at an extraordinary scale, leveraging it consistently outperforms alternatives in the long run. I've stolen some slides from this great presentation by Hyung Won Chung to illustrate my point

However, it's crucial to note that at any given time, you have a finite amount of available compute. Blindly removing structure from your model isn't always optimal. You should build in such a way that inductive biases are easy to remove, as your available compute grows!

I'd like to exemplify the bitter lesson by looking at how the transformer architecture has changed through the past 8 years since its release. What happened to encoder-only and encoder-decoder structures? Why are all language models decoder-only today? If you were around in 2018/19, you'll remember the craze that surrounded BERT models, and one might ask themselves why we never scaled BERT models to the size of GPT-style models we have today.

Let's take a closer look at the three prominent transformer architectures: encoder-only, decoder-only and encoder-decoder.

Encoder-Decoder Architecture

The original Attention is all you need paper proposed the encoder-decoder architecture for machine translation. Here's how it works:

- Encoder: Processes the input sequence A, creating a high-dimensional representation.

- Decoder: Takes the (so far) translated sentence B as input.

- Cross-Attention: Connects the encoder and decoder, allowing the decoder to focus on relevant parts of the input sequence.

- Output: Generates the next token in an autoregressive fashion, extending sequence B.

At the time, this was groundbreaking for machine translation. The encoder could capture the full context of the input sentence, while the decoder could generate fluent translations token by token.

However, this architecture has some limitations:

- It's complex to apply to tasks other than sequence-to-sequence problems.

- The strict separation between encoder and decoder can be inefficient for some tasks.

- It requires maintaining two separate sets of parameters, which can be computationally expensive at scale.

Despite these drawbacks, encoder-decoder models still shine in specific applications like machine translation and summarization, where the input and output sequences are fundamentally different.

Encoder-Only Architecture (BERT)

BERT was introduced as an encoder-only architecture that, instead of autoregressive pretraining, adopted a denoising objective (fill in the blank). The encoder-only architecture outputs a single vector that encodes the input sequence, which is used as input to a task-specific linear layer that maps it to a classification label space.

This was a lot easier than outputting a sequence! We restrict the output space, modelling assumptions about the type of output which lead to huge leaps in the NLP field. This is an excellent example of inductive bias helping for a given compute budget.

BERT was pre-trained on a large internet corpus, and then the classification heads were fine-tuned for each specific downstream task. As I said, this modelling led to many, many benchmark improvements over the years 2018-2020. But, as one might expect, not generating sequences is a deal-breaker for a general use case. BERT-style models were cumbersome to work with, and the interest for multi-task models grew large enough that people ultimately moved away from BERT. Task fine-tuning was finicky and took a lot of time.

Decoder-Only Architecture (GPT-style)

There was a transition back to sequence-to-sequence models, and this is where decoder-only models really took off.

It was the realization that you could concatenate input and target sentences, creating a self-supervised sequence-in-sequence-out model that truly enabled decoder-only:

- A unified sequence processing that removes the structural bias of having distinct input processing and output generation.

- The separate cross-attention modality in the encoder-decoder structure is baked into the causal self-attention, allowing attention to the entire sequence, without assumption of input / output.

- The same parameters are applied to input and target sequences.

- Next-token prediction removes task-specific bias, enabling more general latent representations.

By removing these structural biases, decoder-only models align more closely with the bitter lesson: they make fewer assumptions about the nature of language and instead rely on scale to learn these patterns from data.

There are additional benefits to these GPT-style models that make them scale better, leveraging computation at its utmost:

-

The causal language modelling objective is extremely efficient compared to the denoising objective of BERT. In denoising, only a small percentage of the total tokens are being masked and hence "used" to generate loss. Conversely, the causal LM objective makes use of nearly 100% of the available tokens.

-

During inference, decoder-only models don't need to re-compute representations for every token because they don't depend bidirectionally. This means we can cache these (kv cache) and trade memory for compute.

-

The next-word prediction task forces the model to build robust, general-purpose representations, which is the primary objective of language model pretraining. The better the internal representations, the easier it is to use these learned representations for tasks.

To illustrate this last point, imagine training a language model on the sentence:

The Eiffel Tower stands 324 meters tall in Paris, France

using next-word prediction. You're obviously training the model to learn proper grammar, but there's so much more baked into such a simple sentence:

- "The [Eiffel Tower]" : World knowledge

- "The Eiffel Tower [stands]" : Contextual understanding (appropriate verb for structures)

- "The Eiffel Tower stands [324]" : Numerical knowledge (specific fact)

- "The Eiffel Tower stands 324 [meters]" : Unit of measurement

- "The Eiffel Tower stands 324 meters [tall]" : Language understanding (adjective for height)

- "The Eiffel Tower stands 324 meters tall in [Paris]" : World knowledge

- "The Eiffel Tower stands 324 meters tall in Paris[,]" : Syntax

- "The Eiffel Tower stands 324 meters tall in Paris, [France]" : World knowledge

This is what makes the next-word prediction / causal language modelling objective into a massively multi-task learning objective. As we scale up the model size and training data, this multi-task learning becomes increasingly powerful, allowing the model to capture more complex and nuanced aspects of language and knowledge.

By embracing the bitter lesson - removing structural assumptions and relying on scale - decoder-only, GPT-style models have become the bread and butter of large language models.