making sense of floating points

March 21, 2024

NVIDIA GTC has just passed and with it came the announcement of their new architecture 'Blackwell'. It seems that Jensen's way of outpacing Moore's Law is just to reduce precision: "Blackwell is up to 30x faster than Hopper with over 20 petaflops of FP4 power". FP4. That's 16 numbers. It's funny to imagine a functioning representation scheme with just 16 numbers, i mean you can hold the entire set in a 2 byte lookup table!

Floating point numbers was something I just took at face value for a long time, I tried wrapping my head around them but I always rejected the mathematical notation and things never stuck

But some time ago, i read an explanation that just made sense, things clicked, and eventually the formula above no longer terrified me. If you're like me, and you've put off understanding floating points, today might be the day that things click for you to!

An attempt at a intuitive explanation of FP32

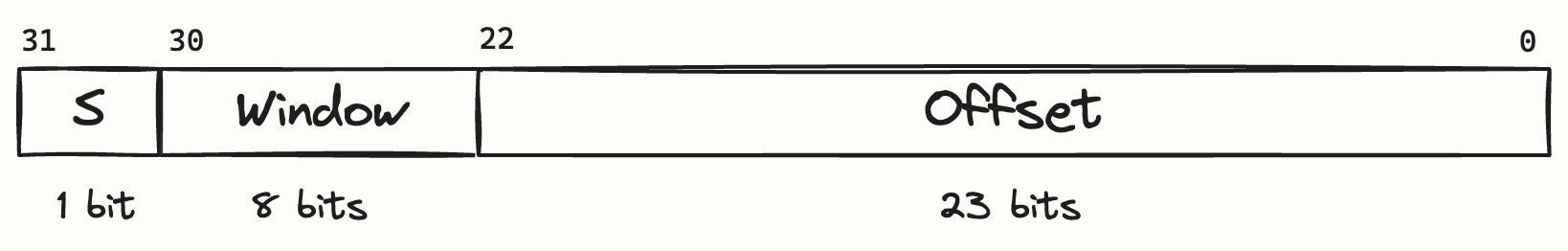

Let's start of with the classic 32-bit floating point, as defined by IEEE 754. You've probably got the words exponent, mantissa and significand stored somewhere in memory, hoping not to have to think about them again, but if we ignore those for now and imagine a 32-bit floating point defined like this:

Our floating point is represented by a sign bit S, 8 window bits and 23 offset bits. Now, initially it might look like I've just slapped new words on already complicated things, but bare with me. The first bit, the sign bit, is the easiest, when its 0 your number is positive and when its 1, the number is negative. The window defines in between which consecutive power-of-two's a number lies: [, ], [, ] and so on up to [, ]. Example: to represent 1000, you find the window [, ] = [512,1024]. Finall, the offset bits divides each of these windows into frames, that enable you to approximate a floating point number.

You might have already noticed that the windows grow exponentially in size, while the number of frames remain constant. The consequence is that our precision is reduced for larger numbers.

An example

I think the best way to learn is through an example. How do we represent the number ?

- The number is positive so our sign bit is 0.

- Which window is in? It lands between and , and therefor our window bits should represent (think window start + offset = number)

- Finally, we need to find the frame that is the closest approximation of our desired number. We find that the offset ratio is , which when translated to our mantissa range gives . Notice that this isn't a whole number, but we said that we divided our range into exactly frames. This means we have to round up to , and this represents our precision error!

Did we get things right? Well let's go back to the original formula.

- The sign bit, S, is the same

- The mantissa, , is our offset.

- Our window is the exponent, .

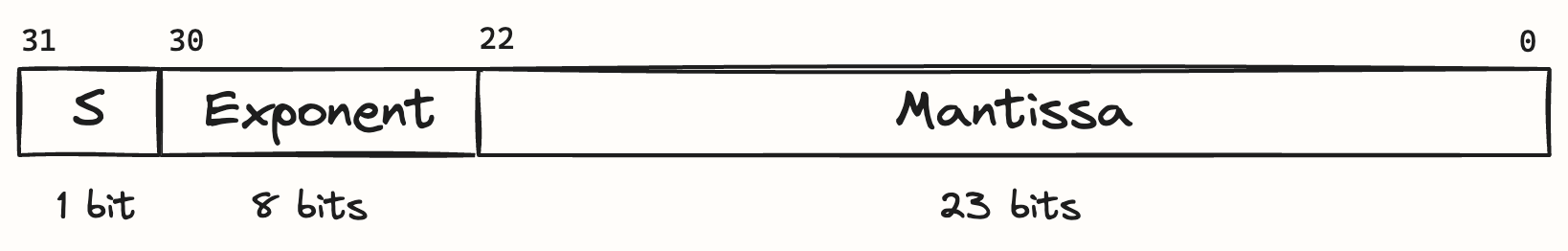

Going back to the original definition

Now that things (hopefully) make sense, going we can go back to the original definition of a floating point.

The exponent refers to the exponent in the formula

which we called the window. Notice how the exponent defines a power-of-two. The reason you subtract 127 (called the bias) is because we want to be able to represent numbers between and as well, and for that we need negative exponents. The 8 bits used for the exponent can represent integers up to 255, but with the bias implemented we shift the exponent to [,]. The Offset is called the Mantissa, often denoted with an , and finally the signed bit is the same.

Hopefully you found this alternate explanation a bit more insightful!