training in fp-8

Original paper · Peng et al 2023

Quantization has become a hacker's favorite, acting as a democratizing force in the ever scaling landscape that is modern deep learning. HuggingFace is blowing up with quantized versions of models, readily available for people to try out all thanks to enthusiasts such as TheBloke. This kind of work, known as Post-Training Quantization has proved very effective. There is also Quantization-aware training which integrates quantization directly into the model training recipe. In the original sense of the term, this meant to train a model from the start using quantized weights and activations, for use later during inference. QLoRA falls into this category, by quantizing the base weights of a pretrained model to 8/4 bits then train additional LoRA parameters in half-precision on-top of the base. Anyway, I'm getting off topic; the point is that quantization works but we've always had to accept the performance / memory trade-off. Well, maybe not for much longer? This paper from Microsoft Research proposes a brand new FP8 mixed precision training framework, unlocking 8-bit in weights, gradients, optimizer and distributed training.

Floating Point 8-bit

The FP8 specification was published back in September 2022 and offers two distinct data types, E5M2 and E4M3, which trade-off range and precision. Now, if you're like me (before I read this paper), E5M2 and E4M3 might as well be a gift card redeem code.

- E4M3 consist of 1 sign bit, 4 exponent bits and 3 bits of mantissa. It can store values up to +/- 448.

- E5M2 consist of 1 sign bit, 5 exponent bits and 2 bits of mantissa. It can store values up to +/- 57344.

Okay, so just cast everything to FP8?

FP8 is a natural evolution from the 16-bit data formats to further reducing computing costs. However, training LLMs with reduced-precision FP8 poses new challenges. As described above, the dynamic range and representation precision of FP8 are much lower than BF16 and FP16. This causes repeating cases of data underflow or overflow, which lead to numerical instabilities and irreversible divergences throughout the training process. The authors propose two techniques to deal with these issues: precision decoupling and automatic scaling. The former involves isolating parameters such as weights, gradients and optimizer states from the influence of data precision and assigning reduced precision to components that are not precision sensitive. The latter is used to preserve gradient values within the representation range of FP8 data formats, alleviating underflow and overflow during all-reduce communication. Tensor scaling has historically been pioneered by global scaling techniques, where a single adaptive factor is used to scale gradients across all layers. This has been vital in enabling the widespread adoption of FP16 mixed-precision training, as it meant almost no accuracy drop FP16 training. For the shallower range of FP8 ([1.95E-3, 448] for E4M3 and [1.53E-5, 5.73E+4] for E5M2), the authors suggest an even finer-grained solution with per-tensor scaling instead. The figure below shows that the representation range of FP8 has been large enough to deal with general model training.

The FP8 framework

Precision decoupling and automatic scaling are the foundation for the proposed FP8 mixed-precision strategy for LLM training. We've covered why they are necessary and what they encompass, but how are the techniques applied practically? Well, FP8 optimization includes three key perspectives: FP8 communication, FP8 optimizer, FP8 distributed training - designed to be a simple drop-in replacement for existing 16/32-bit mixed precision counterparts. The core idea is to infiltrate FP8 compute, storage and communication into the whole progress of large model training.

FP8 Gradient and All-Reduce Communication

Creating a mixed-precision training framework, isn't as straight forward as just applying FP8 in every place possible.

In L(arge)LM training, gradients are are communicated across GPUs during the all-reduce operation. Previous scaling strategies are unfortunately not robust enough to handle FP8. Pre-scaling:

divides the gradient, , by the total number of GPUs, , before being summed. When is large, this division can cause data underflow. To mitigate this problem, Post-scaling:

performs the gradient summation first, keeping gradients close to the maximum value of the FP8 data type. On the other hand, this approach encounters overflow issues. This is where the authors propose automatic scaling, a auto-scaling factor , that changes on the fly during training:

This is a per-tensor scaling technique, which involves choosing a suitable scaling factor for a given FP8 tensor. The paper's appendix expands on two options, of which delayed scaling is the preferred choice:

- Just-in-time scaling. Set based on the maximum value of . This process introduces a significant amount of overhead as we need to pass through on every iteration, ultimately reducing the benefits of FP8.

- Delayed scaling. Set based on the maximum value observed in a certain number of preceding iterations. This allows for the full benefits of FP8 but necessitates a storage of a history of maximum values.

Unfortunately, the per-tensor scaling technique entails further complications. The library used to perform the all-reduce operation across GPUs (NCCL) lacks the capability to consider the tensor-wise scaling factors, as we mentioned earlier it's designed for a single adaptive scaling factor for all gradients. To avoid complex reimplementation of NCCL, the authors adhere to this behavior by scaling FP8 gradients using a global minimum scaling factor :

This is shared across GPUs to unify the rescaling of the gradient tensors. All gradient tensors associated with the same weight use the same shared scaling factor to quantize the tensors into FP8 format on all GPUs:

This allows for the standard NCCL all-reduce operation, summing the FP8 gradients across GPUs. This dual strategy of distributed and automated scaling enables FP8 low-bit gradient communication while preserving model accuracy!

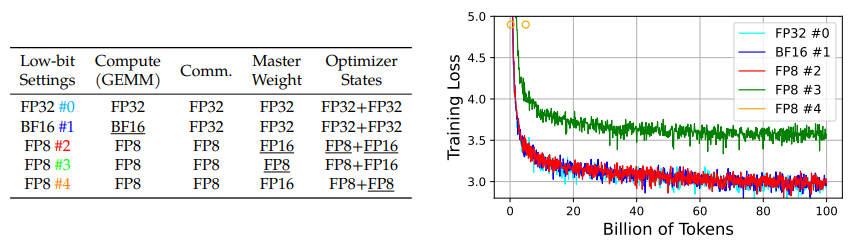

FP8 Optimizer

In mixed-precision training, Adam will consume 16 bytes of memory per parameter: master weights in FP32 (4), gradients in FP32 (4), first-order gradients in FP32 (4) and second-order gradients in FP32 (4). For large models, the optimizer state typically becomes a bottleneck. Previous work has showed that blindly reducing precision of the optimizer to 16-bit leads to accuracy degradation when training billion-scale models. This poses the question of which optimizer states require high precision? To traverse the matter, the authors perform precision decoupling. A fantastic ablation study produces the following results, with precision decoupling defined in the table and respective training loss curves in the figure.

FP8 #2 emerges as the clear winner, offering a excellent reduction in memory. Overall, first-order gradients tolerate a high quantization error and can be assigned with low-precision FP8, while the second-order moment requires a higher precision. This stems from the fact that, during model updates, direction of the gradient is more important than its magnitude. Note that underlined data types include tensor scaling, inferring slight overhead costs.

The master weights require high precision; weight updates can become extremely small and large during training, which means we need the higher precision to prevent loss of information. There are two viable options for their implementation, utilizing FP32 or FP16 with tensor scaling, of which the authors use the latter. The final FP8 mixed-precision optimizer consumes 6 bytes of memory: master weights in FP16 (2), gradients in FP8 (1), first-order gradients in FP8 (1) and second-order gradients in FP16 (2). Overall, their optimizer reduces memory footprint by 2.6x!

FP8 Distributed Training

FP8 supports data parallelism and pipeline paralogism of the shelf, because splitting data batches or model layers into segments across devices does not involve additional FP8 compute or communication. However, both tensor parallelism and the frequently-used distributed learning technique ZeRO require modifications. My gut feeling is that this is going to be a significant hurdle in FP8 LLM adoption. So far, the results have been super impressive, but large scale training often involves parallelism beyond data and pipeline which means it will be a hurdle for teams to incorporate this smoothly into their training pipeline. I won't go over the details but the authors do provide directives on how to adjust for both tensor parallelism and ZeRO, so hopefully it won't be a problem.

Why does even work in the first place?

After all this, you might be wondering how this works in the first place, what is it about neural networks that allows for such low-precision representations? As always, the answer is ambiguous but here's my thoughts on some answers:

- Quantization: The values in neural networks, especially weights, don't cover a broad range uniformly. Many values might be close to zero. This was illustrated earlier in the post with the distribution of gradient activations. Quantization techniques map this non-uniform distribution to a lower precision representation effectively.

- Noise Tolerance: Neural networks, especially deep ones, have persistently shown resilience to noise. In fact, adding noise to activations, weights, or gradients is a common regularization technique. Reduced precision arithmetic can introduce a form of noise, and if the network is large enough, it might be able to tolerate or even benefit from it.

- Mixed Precision Training: As you've noticed, this isn't a pure 8-bit framework because that would be infeasible. What's been done here is implement a smart, mixed-precision framework that employs low-precision formats whenever possible. Lowering overall memory footprints substantially without destroying performance.

In the end, there's always a trade-off to be had but FP8 LLM is the first work in what hopefully is a line of many where we explore the boundaries of memory and cost reductions, democratizing the Large part of language modelling research.