Reward is enough

Original paper · Silver et al 2021

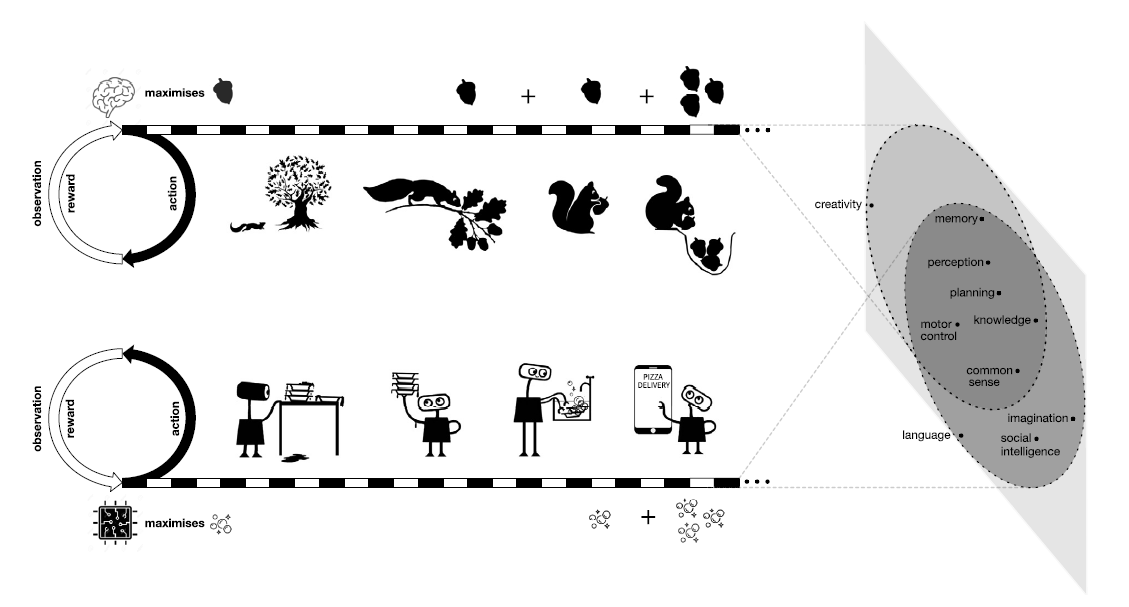

*Hypothesis (Reward-is-Enough): Intelligence, and its associated abilities, can be understood as subserving the maximisation of reward by an agent acting in it's environment.*

This hypothesis was postulated almost three years ago now, it remains to this day highly contentious but its implications are too fascinating to ignore. LLMs are the most recent example of models capturing a wide set of abilities from the scalar language modelling objective. I found this paper to be particularly intriguing to read now, given what has happend since 2020. What would it mean if this type of training objective translates to general intelligence as well?

Reward - the ultimate learning objective

Intelligence is manifold, it presents itself in all kinds of environments, and under varying conditions. What could it be that drives agents (whether natural or atificial) to behave intelligencly in such a diverse vareity of ways? Well the authors of this paper propose that the generic objective of maximising reward is enough for the emergence of intelligent behaviour to occur. It may sound like an oversimplification, how would the pursuit of a single goal explain the diversity of intelligence observed in our environment alone? Well, given the inherently complexity of natural environments, they would require sophisticated abilities in order to suceed. This leads us to believe that different environments call for different reward signals, all of which ultimately culminate in intelligent beings with distinct abilities such as tool use in chimpanzees, planning in squirells, communication in dolphins.

Intelligence of a single being is often attributed to the aggregation of multiple abilities. According to the authors, all of these abilities subserve a singular goal of maximising the agents reward within its environment. As an example, a kitchen robot implemented to maximize cleanliness will, given time and capacity, learn to percieve, move, rememeber etc as sub-goals in its overarching maximisation. The authors don't touch on this too much but time and capacity are determinant in the intelligence that will emerge. Capacity explains why humans are more intelligence than any other being and time explains how any being is intelligent in the first place. In the context of artificial agents, time can be manipulated and capacity can be scaled but this shifts the problem to one of computational resources.

How to achieve reward maximisation

A natural question after establishing the hypothesis is how should one go about maximizing the reward of an agent. There are many approaches to this problem the most intuitive of which to learn to do so, by interacting with the environment in a trial and error fashion. This is remeniscent of how knowledge in all natural agents grows, ignoring that which is biologically implanted. Learning to hunt is a means of which to achieve satiation, not the other way around. We didn't learn to hunt only to then realise it could satisfy our nutritional needs. In artificial intelligence, this concept was undisputably demonstrated in Chess by AlphaZero. Previous approaches to chess agents largely focussed on specific abilities such as openings, end-game, and strategy each involving different objectives. AlphaZero on the other hand, focused simply on a singular goal: maximisizng the reward signal at the end of the game. This, together with highly effective search algorithms and exorbitant amounts of self-play (time and capacity) resulted in the most robust Chess engines we have today. Not only this but it also heightened our understanding of openings and piece mobility. The beutiful thing about reinforcement learning is it's ability to venture along trajectories not previously considered.

Reinforcement learning agents

A prevailing belief suggests that a robust reinforcement learning agent can evolve to exhibit complex cognitive abilities, mirroring what we perceive as intelligence. Essentially, if an agent can adapt its strategies to consistently improve its cumulative rewards, the essential skills demanded by its environment inevitably manifest in its actions. So, in an environment as multifaceted as the human realm, an adept reinforcement learning agent might organically acquire behaviors representative of perception, language, and even social intelligence - all as part of its quest to augment rewards.

Recent examples like AlphaZero underscore this. In mastering games like Go and chess, it developed intricate game-specific strategies. Other agents, designed for Atari 2600, exhibited skills from object recognition to motor control. While these challenges may seem narrow compared to natural complexities, they undoubtedly highlight the power of the reward-maximization principle.

Interestingly, there's a notion that only a meticulously designed reward can cultivate general intelligence. Contrarily, we're led to believe that intelligence's emergence might be considerably resilient to variations in the reward's nature. The intricacies of vast environments, like our natural world, might necessitate the development of intelligent behaviors even under the influence of the simplest reward signals.

What about unsupervised and supervised learning?

Unsupervised learning may seem like a promising approach to general intelligence given the success of foundational models. UL identifies patterns within observations and is effective for understanding experiences. However, the methodology falls short in one crucial aspect: it doesn't inherently offer mechanisms for goal-oriented actions, making it inadequate for comprehensive intelligence in isolation.

Supervised learning, on the other hand, has been hailed for its capacity to emulate human intelligence. Given a vast array of human data, it seems plausible that a model could replicate every nuance of our cognitive abilities. Yet, it bears its limitations. Solely relying on human data, supervised learning struggles to cater to objectives that venture beyond human-centric goals or environments. There's an inherent boundary: its capability is anchored to the behaviors already recognized and demonstrated by humans in the training data. This results in an inability to innovate or think outside the confines of the data.

A notable shift, as observed in recent NLP studies, is that models benefit significantly from the amalgamation of reinforcement learning and human feedback. While supervised learning might traditionally be limited by its training data, including its inconsistencies, reinforcement mechanisms, when coupled with human insights, can transcend these boundaries, aligning outputs closer to human preference and even fostering trajectories that might be unforeseen by human annotators.