Training Compute-Optimal Large Language Models

Original paper · Hoffmann et al 2022

As we approach the present, the volume of seemingly relevant papers increases exponentially. It becomes more challenging to identify seminal works because time has not yet distinguished them and as a result I'm left unsure what papers I should tackle next. One part of me wants to follow through and completely go through all text-based LLMs up to the present, another wants to move into the multi-modal space starting with the Visual Transformers and another part of me wants to look more into dialogue based models such as InstructGPT and LaMDA. We'll see where we go from here but for now it seemed natural to take on DeepMind's second LLM - Chinchilla - a perfect follow up to the Gopher paper. Before we get started I have to say what a pleasure it was to read this paper, it's so well written, the contributions are clear and the paper is structured perfectly for what they are trying to argue... yeah really fun read and the implications of this paper seem wild(!). I really can't stress enough how much this paper did for the field, the authors trained over 400 GPT-style transformers ranging from 70M-16B parameters and performed proper ablation studies finding usable scaling laws that accelerated the field immensely.

Scaling Laws

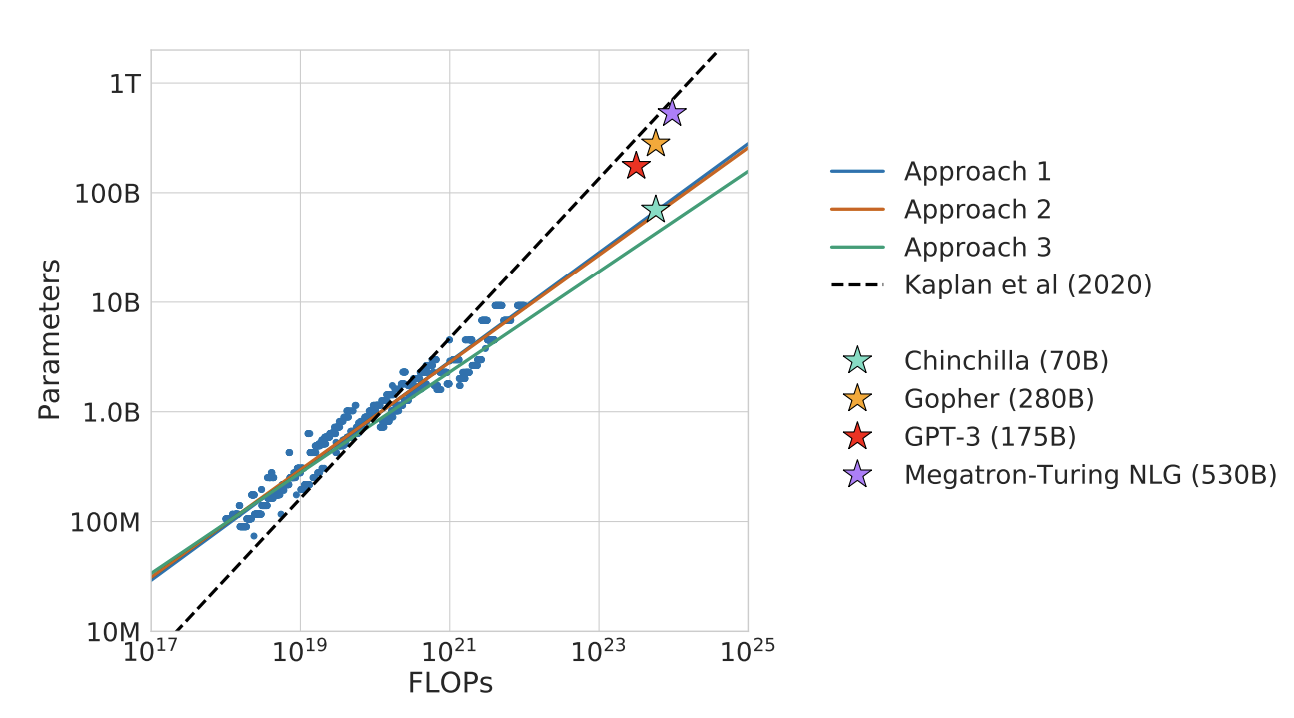

While the model presented in this paper is indeed Chinchilla, the main motivation is actually an investigation of optimal model size and training tokens ultimately leading to new scaling laws. You might recall that OpenAI published a paper back in 2020 where a number of scaling laws were established, I covered that paper on this blog and it's one of the reasons why the field has been pushing to train larger and larger models stretching 2019-2022. Notably they found that given a 10x computational budget increase model size should increase 5.5x and training tokens 1.8x. DeepMind present three different approaches to answer how one should trade-off model size and number of training tokens given a fixed compute budget. The resulting predictions are similar for all three methods and clearly suggest that model size and training tokens should be increased equally with more compute.

The figure shows the three approaches overlaid with projections from Kaplan et al. It is clear how overdimensioned the well established models are given their compute budget. Most models at the time were trained on 300B tokens which, given these scaling laws was a huge limitation of their capabilities. Furthermore the authors fit the following equation to their results:

where E is the "irreducible loss" that is inherent to the training dataset achieved if one where to train an infinitely big model on infinite data. The other two terms account for the fact that a model only has N parameters and the model only sees D training tokens. Given the MassiveText dataset created by DeepMind for this project, the authors find the optimal model to be

Again, we see the the equilibrium required between model size and data size.

Chinchilla

Based on the estimated compute-optimal frontier, Gopher should be 4 times smaller given the same compute budget, while being trained for 4 times more tokens. The authors prove this theory by training a model using such configuration, Chinchilla. Without using any more compute the authors are able to steadily improve downstream performance across most evaluated tasks. What's even more interesting - if we assume the parametric scaling laws presented in Approach 3 are correct then Chinchilla will beat any model trained on Gopher's data, no matter how big. This really puts into context how big of an impact these scaling laws have as it would mean an entire line of research could never have beaten Chinchilla.